Cervical cancer refers to neoplasia arising from the cervix – the lower part of the uterus. It is the third most common cancer worldwide, and the 12th most common in the UK.

In 2012, cervical cancer was responsible for 266,000 deaths worldwide. Unlike many cancers, it is primarily a disease of the young; half of all cases are diagnosed before the age of 47, with a peak age of diagnosis in those aged 25-29. There is a second peak in women in their 80s.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of cervical cancer.

Aetiology and Pathophysiology

The majority (70%) of cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinomas. Of the remainder, 15% are adenocarcinoma and 15% are mixed in type.

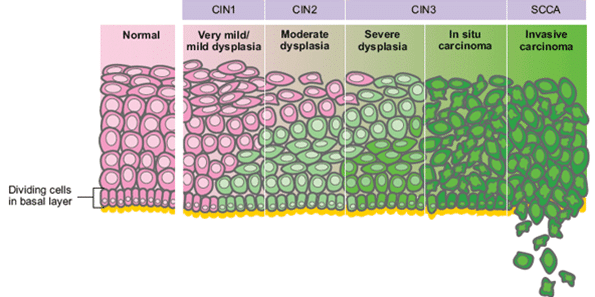

Cervical cancer usually develops as a progression from cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). This occurs over the course of 10-20 years, although not all cases of CIN progress to cancer (and most spontaneously regress).

Invasive cervical cancer occurs when the basement membrane of the epithelium has been breached. The most common sites of metastasis are the lung, liver, bone and bowel.

The vast majority of cervical squamous cell cancers are caused by persistent human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Indeed, 99.7% of cases contain HPV DNA within the cancerous cells.

Fig 1 – Cervical cancer usually develops as a progression from cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN).

Human Papilloma Virus

The human papilloma virus is a sexually transmitted virus which affects the skin and mucous membranes. There are more than 100 different strains, of which around 30 affect the genital area.

HPV is highly prevalent, with around 80% of women thought to be infected at some point. However, the majority of infections are cleared by the immune system within 2 years. Some cases persist, and these can go on to cause malignant changes such as CIN and cervical cancer over a course of many years.

Not all HPV types are oncogenic. HPV 6 and 11 are low-risk serotypes that cause genital warts and are unlikely to cause cancer. The most common high risk serotypes are 16 and 18. They are thought to produce proteins which inhibit the tumour suppressor protein p53 in cervical epithelial cells, allowing for uncontrolled cell division.

In the UK, the National HPV vaccination programme provides protection against HPV 16 and 18 (the cause of 70% of cervical cancer cases), as well as HPV 6 and 11. The combination of screening and vaccinations are thought to account for a 40% reduction in incidence in the UK, and prevent roughly 2000 deaths per year.

Risk Factors

As discussed above, infection with human papilloma virus is the greatest risk factor for cervical cancer. Other risk factors include:

- Smoking

- Other sexually transmitted infections

- Long-term (> 8 years) combined oral contraceptive pill use

- Immunodeficiency (e.g. HIV)

Clinical Features

The most common presenting symptom of cervical cancer is abnormal vaginal bleeding (e.g post-coital, intermenstrual or post-menopausal). Other clinical features include vaginal discharge (blood-stained, foul-smelling), dyspareunia, pelvic pain and weight loss.

However, it is often asymptomatic – particularly in the early stages of disease – and many cases are detected through routine screening.

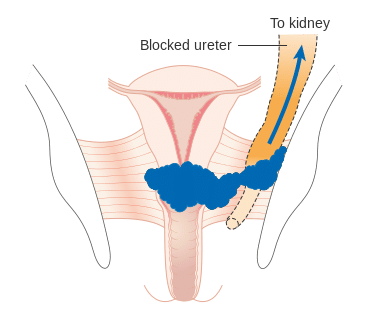

In advanced disease, the patient may experience oedema, loin pain, rectal bleeding, radiculopathy and haematuria. These often occur as a result of the cancer invading into nearby structures.

A thorough clinical examination is required in cases of suspected cervical cancer and includes:

- Speculum examination – assess for evidence of bleeding, discharge and ulceration.

- Bimanual examination – assess for pelvic masses.

- GI examination – assess for hydronephrosis, hepatomegaly, rectal bleeding, mass on PR.

Differential Diagnoses

There are a large number of possible causes for abnormal vaginal bleeding. These include sexually transmitted infection, cervical ectropion, polyp, fibroids, and pregnancy related bleeding.

In the post-menopausal population, always exclude endometrial carcinoma.

Investigations

In a woman presenting with symptoms suggestive of cervical cancer, the initial investigation depends on age:

- Pre-menopausal – test for chlamydia trachomatis infection

- If positive; treat for chlamydia infection. If symptoms persist after treatment, refer for colposcopy and biopsy.

- If negative; a colposcopy and biopsy is usually performed.

- Post-menopausal – urgent colposcopy and biopsy.

A colposcopy is where a colposcope (modified microscope) is used to produce a magnified view of the cervix. Acetic acid is used to stain dysplastic areas, and a biopsy is taken.

If the diagnosis of cervical cancer is confirmed, further investigations are required:

- Basic blood tests – such as full blood count, liver function tests and urea & electrolytes

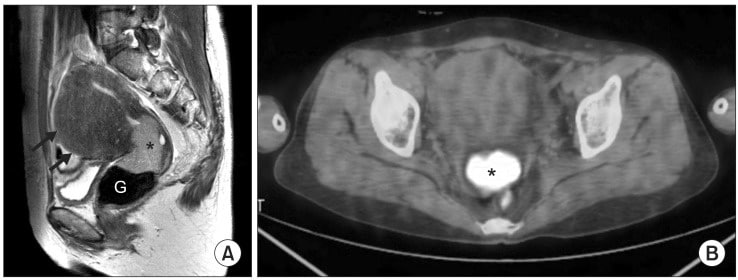

- CT Chest-Abdomen-Pelvis – looking for metastases.

- Further staging scans – e.g. MRI pelvis, PET.

- +/- examination under anaesthesia with further biopsies.

Note: The cervical cancer screening programme aims to detect pre-invasive disease (i.e CIN). Cervical smears are not used to detect cervical cancer.

Fig 3 – T2-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance (MR) image obtained prior to concurrent chemoradiation therapy shows hyper intense cervical cancer (asterisk) in the cervical canal.

Staging

The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging system is used for cervical cancer:

- Stage 0 – Carcinoma in-situ

- Stage 1 – Confined to cervix

- A) Identified only microscopically.

- B) Gross lesions, clinically identifiable.

- Stage 2 – Beyond cervix but not pelvic sidewall/ involves vagina but not lower 1/3

- A) No parametrial involvement.

- B) Obvious parametrial involvement.

- Stage 3 – Extends to pelvic sidewall/ involves lower 1/3 vagina/ hydropnephrosis not explained by another cause.

- A) No extension to sidewall.

- B) Extension to sidewall and/or hydronephrosis.

- Stage 4 – Extends to bladder or rectum, or metastases

- A) Involves bladder/rectum.

- B) Involves distant organs

Management

In the management of cervical cancer, it is important to consider the stage of disease, co-morbidities and fertility issues when deciding on treatment.

As with all cancers, treatment involves multidisciplinary input. Possible options include surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.

Surgical Options

The available surgical options are dependant on the stage of the cancer:

Stage 1a

Radical trachelectomy if fertility-preservation is a priority. This involves removal of the cervix and upper vagina. Otherwise, a laparoscopic hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy is offered.

Stage 1b/2a

Radical (Wertheim’s) hysterectomy as a curative treatment modality. Involves removal of the uterus, vagina and parametrial tissues up to the pelvic sidewall, plus lymphadenectomy.

Stage 4a or Recurrent disease

Anterior/posterior/total pelvic extenteration. Removal of all pelvic adnexae plus bladder (anterior)/rectum (posterior or both (total).

Radiotherapy

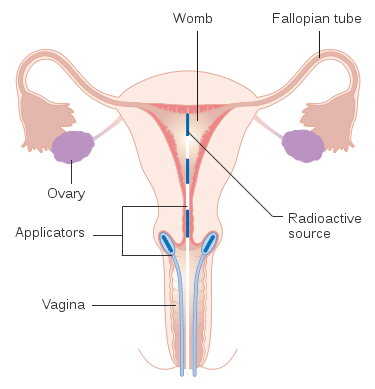

Radiotherapy is often a combination of external beam therapy and intracavity brachytherapy. If offers an acceptable alternative to surgery in early-stage disease.

Stage 1b to 3

Offered in conjunction with chemotherapy over a 5-8 week course. Evidence suggests additional hysterectomy offers no benefits in terms of survival for these stages. Therefore chemoradiation therapy is the gold standard.

Fig 4 – Radiotherapy can be delivered in the form of intracavity brachytherapy.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy in cervical cancer is often cisplatin-based.

It can be given before treatment by surgery or radiotherapy (known as neoadjuvant chemotherapy), or after treatment (adjuvant chemotherapy).

It is also the mainstay of treatment in the palliative setting.

Follow-Up

Patients should be reviewed by a gynaecologist every 4 months after treatment has been completed for the first 2 years, and every 6-12 months for the subsequent 3 years.

All follow-ups should involve a physical examination of the vagina and cervix (if they haven’t been removed).

Note – Cervical smear testing is no longer valid after radiotherapy.