Lichen sclerosus is a chronic inflammatory skin disease of the anogenital region in women.

It has a bimodal incidence, peaking in prepubescent girls and post-menopausal women. Although uncommon, it can be a debilitating disease – which has the potential to progress to squamous cell carcinoma (~5% of the postmenopausal group).

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of lichen sclerosus.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

The cause of lichen sclerosus is largely unknown. Patients with lichen sclerosus have a higher titre of antibodies to extracellular matrix protein 1 [Lancet, 2003] – which suggests a possible autoimmune aetiology.

The risk factors for lichen sclerosus include:

- Genetics – family history of lichen sclerosus can increase risk.

- Other autoimmune disorders – such as thyroid disease, type 1 diabetes, alopecia areata.

Upon microscopy, lichen sclerosus characteristically causes atrophy; producing a thin stratified squamous epithelium. A band-like infiltrate of chronic inflammatory cells can be observed beneath this epithelial layer.

Clinical Features

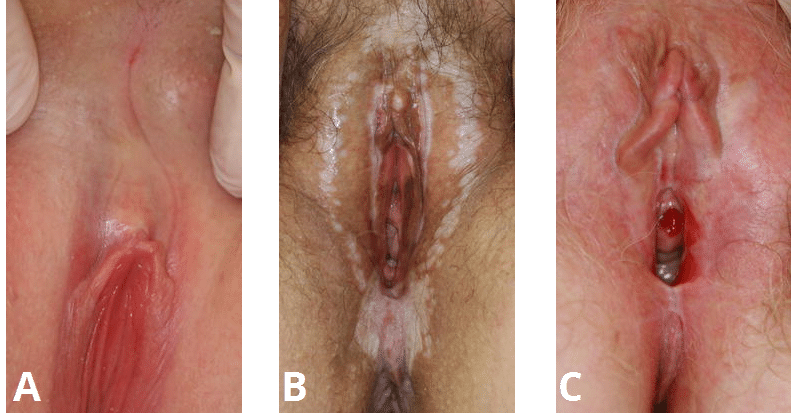

Lichen sclerosus typically appears as white atrophic patches on the skin, usually within the anogenital region. It can occur elsewhere on the body (such as axillae, buttocks and thighs) – but this is rare.

The most common symptom is itching, and the skin may undergo fissuring or erosions – which can cause pain. The majority of sexually active women will experience dyspareunia. However, it is important to note that some patients are asymptomatic.

On examination, the white lesions of lichen sclerosus are characteristically well defined, with evidence of adhesions and/or scarring, such as:

- Clitoral hood fusion

- Fusion of the labia minora to the labia majora

- Posterior fusion resulting in loss of vaginal opening

Differential Diagnoses

In cases of suspected lichen sclerosus, the common other differential diagnoses include:

- Lichen simplex

- Vitiligo

- Vulvae cancer or intraepithelial neoplasia

- Candidiasis

- Post-inflammatory hypopigmentation

Investigations

The diagnosis of lichen sclerosus is usually made clinically, with no investigations required. Often it is preferable to test by treating and assessing any response.

A biopsy can be performed if there is uncertainty about the diagnosis – especially in cases of treatment failure, or when malignancy needs to be excluded.

Management

The mainstay of management of lichen sclerosus is with immunosuppression. Patients should be given advice regarding avoiding irritants to the area, and minimising urinary contact.

First line therapy is the use of topical steroids, such as clobetasol propionate. In the UK, the recommended regime is once daily at night for 4 weeks, then on alternate nights for 4 weeks, and then twice weekly for a further 4 weeks.

Patients with lichen sclerosus should be followed-up, as there is a risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma in chronic cases (2-5% lifetime risk).