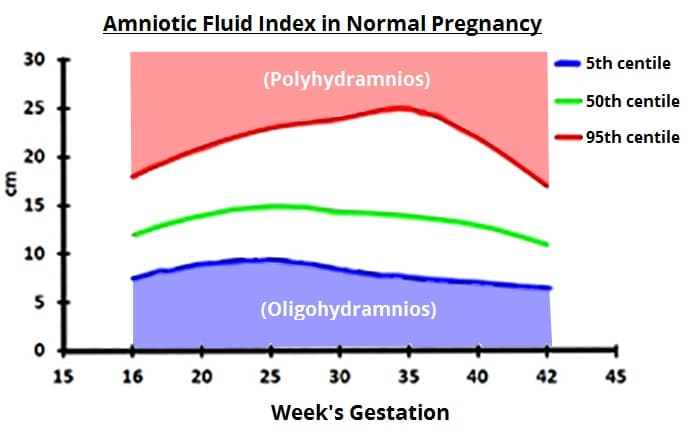

Polyhydramnios refers to an abnormally large level of amniotic fluid during pregnancy.

It is defined by an amniotic fluid index that is above the 95th centile for gestational age.

In this article, we shall look at the causes, clinical assessment and management of polyhydramnios.

Fig 1 – Amniotic fluid centiles during pregnancy. Polyhydramnios is over the 95th centile, oligohydramnios is below the 5th centile

Pathophysiology

The volume of amniotic fluid increases steadily until 33 weeks of gestation. It plateaus from 33-38 weeks, and then declines – with the volume of amniotic fluid at term approximately 500ml.

It is predominantly comprised of the fetal urine output, with small contributions from the placenta and some fetal secretions (e.g. respiratory, oral).

The fetus breathes and swallows the amniotic fluid. It gets processed, fills the bladder and is voided, and the cycle repeats. Problems with any of the structures in this pathway can lead to either too much or too little fluid.

Aetiology

Polyhydramnios is idiopathic in 50-60% of cases. Where an underlying abnormality can be identified, the most common causes include:

- Any condition that prevents the fetus from swallowing – e.g. oesophageal atresia, CNS abnormalities, muscular dystrophies, congenital diaphragmatic hernia obstructing the oesophagus

- Duodenal atresia – ‘double bubble’ sign on ultrasound scan

- Anaemia – alloimmune disorders, viral infections

- Fetal hydrops

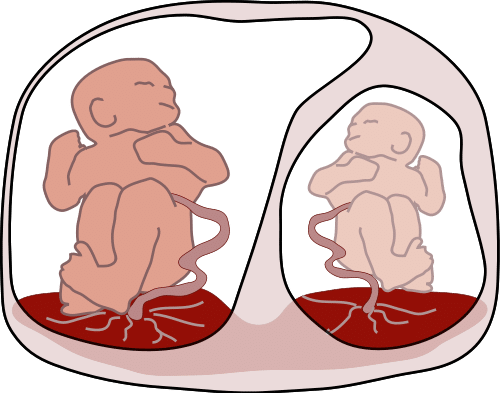

- Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome

- Increased lung secretions – cystic adenomatoid malformation of lung

- Genetic or chromosomal abnormalities

- Maternal diabetes – especially if poorly controlled

- Maternal ingestion of lithium – leads to fetal diabetes insipidus

- Macrosomia – larger babies produce more urine.

Fig 2 – Twin to twin transfusion syndrome, a complication of a disproportionate blood supply in twin pregnancies. It is a cause of polyhydramnios.

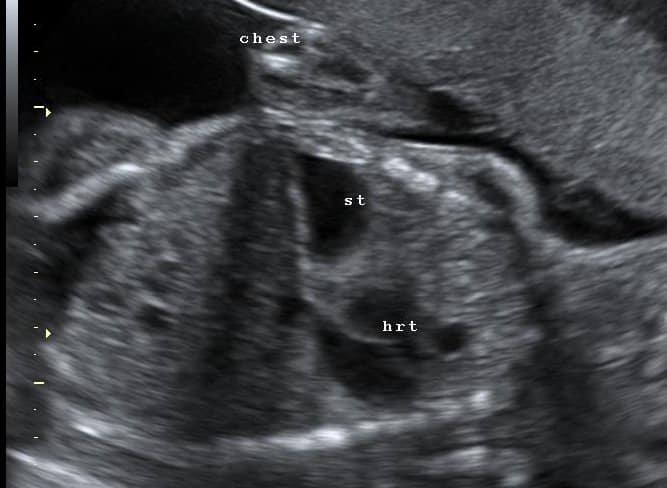

Diagnosis of Polyhydramnios

The diagnosis of polyhydramnios is made via ultrasound examination. There are two ways of measuring amniotic fluid; amniotic fluid index (AFI) or maximum pool depth (MPD). They have similar diagnostic accuracy, however AFI is more commonly used.

- Amniotic fluid index is calculated by measuring maximum cord-free vertical pocket of fluid in four quadrants of the uterus and adding them together.

- Maximum pool depth is the vertical measurement in any area.

Clinical Assessment

Polyhydramnios is a diagnosis made via ultrasound examination. Therefore, the clinical assessment of the patient is directed at establishing any underlying cause:

- Examination

- Palpate the uterus – does it feel tense?

- Ultrasound

- Repeat measurement of liquor volume

- Assess fetal size

- Assess fetal anatomy to detect any structural causes

- Doppler – to detect fetal anaemia

- Maternal glucose tolerance test – for maternal diabetes

- Karyotyping (if appropriate) – especially if other structural abnormalities are detected, or if the fetus is small.

Some viral infections can cause polyhydramnios. Therefore, a TORCH (Toxoplasmosis, Other (Parvovirus), Rubella, Cytomegalovirus, Hepatitis) screen should be undertaken. Maternal red cell antibodies should also be checked; in the UK this is performed routinely at 28 weeks for all pregnancies.

Management

No medical intervention is required in the majority of women with polyhydramnios.

If the maternal symptoms are severe (e.g breathlessness), an aminoreduction can be considered. It is associated with infection and placental abruption (due to a sudden decrease in intrauterine pressure), and is therefore not performed routinely.

Indomethacin can be used to enhance water retention, and thus reduces fetal urine output. It is associated with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus and therefore should not be used beyond 32 weeks.

In cases of idiopathic polyhydramnios, the baby must be examined before its first feed by a paediatrician. A nasogastric tube should be passed to ensure there is not a tracheoesophageal fistula or oesophageal atresia.

Prognosis

Severe and persistently unexplained polyhydramnios is associated with increased perinatal mortality. This is largely due to two factors:

- The likely presence of an underlying abnormality or congenital malformation.

- The increased incidence of preterm labour (due to over-distension of the uterus).

Malpresentation (e.g. transverse lie, breech presentation) is also more likely – as the fetus has more room to move within the uterine cavity. Care must be taken at rupture of membranes, as there is a higher risk of cord prolapse.

After delivery, there is a higher incidence of postpartum haemorrhage, as the uterus has to contract further to achieve haemostasis.

Summary

- Polyhydramnios is the presence of amniotic fluid >95th centile.

- The main cause for this is idiopathic, but structural, viral and diabetes as causes must be investigated for.

- The prognosis is usually good, with only 1% of structurally normal fetuses on ultrasound having an associated congenital abnormality.