A Caesarean section is the delivery of a baby through a surgical incision in the abdomen and uterus.

In this article, we shall look at the classification of Caesarean sections, its indications, and an outline of the operative procedure.

Classification

A Caesarean section can be classified as either ‘elective’ (planned) or ‘emergency’.

Emergency Caesarean sections can then be subclassified into three categories, based on their urgency. This is to ensure that babies are delivered in a timely manner in accordance to their or their mother’s needs.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) recommends that when a Category 1 section is called, the baby should be born within 30 minutes (although some units would expect 20 minutes). For Category 2 sections, there is not a universally accepted time, but usual audit standards are between 60-75 minutes.

Emergency Caesarean sections are most commonly for failure to progress in labour or suspected/confirmed fetal compromise.

| Category | Description |

| 1 | Immediate threat to the life of the woman or fetus |

| 2 | Maternal or fetal compromise that is not immediately life-threatening |

| 3 | No maternal or fetal compromise but needs early delivery |

| 4 | Elective – delivery timed to suit woman or staff |

Indications

A planned or ‘elective’ Caesarean section is performed for a variety of indications. The following are the most common, but this is not an exhaustive list:

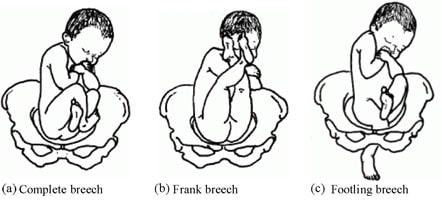

- Breech presentation (at term) – planned Caesarean sections for breech presentation at term have increased significantly since the ‘Term Breech Trial’ [Lancet, 2000].

- Other malpresentations – e.g. unstable lie (a presentation that fluctuates from oblique, cephalic, transverse etc.), transverse lie or oblique lie.

- Twin pregnancy – when the first twin is not a cephalic presentation.

- Maternal medical conditions (e.g. cardiomyopathy) – where labour would be dangerous for the mother.

- Fetal compromise (such as early onset growth restriction and/or abnormal fetal Dopplers) – where it is thought the fetus would not cope with labour.

- Transmissible disease (e.g. poorly controlled HIV).

- Primary genital herpes (herpes simplex virus) in the third trimester – as there has been no time for the development and transmission of maternal antibodies to HSV to cross the placenta and protect the baby.

- Placenta praevia – ‘Low-lying placenta’ where the placenta covers, or reaches the internal os of the cervix.

- Maternal diabetes with a baby estimated to have a fetal weight >4.5 kg.

- Previous major shoulder dystocia.

- Previous 3rd/4th degree perineal tear where the patient is symptomatic – after discussion with the patient and appropriate assessment.

- Maternal request – this covers a variety of reasons from previous traumatic birth to ‘maternal choice’. This decision is after a multidisciplinary approach including counselling by a specialist midwife.

Elective Caesarean sections are usually planned after 39 weeks of pregnancy to reduce respiratory distress in the neonate – known as Transient Tachypnoea of the Newborn (TTN).

For those where delivery needs to be expedited prior to 39 weeks’ gestation, the administration of corticosteroids to the mother should be considered. This stimulates development of surfactant in the fetal lungs.

Theatre Procedure

Pre-Operative

Before a Caesarean section, there are a number of basic steps that should be performed:

- Full blood count (FBC) and a Group and Save (G&S) should be taken.

- The average blood loss at Caesarean section is approximately 500-1000ml, depending on many factors, especially the urgency of the operation.

- H2-receptor antagonist should be prescribed – e.g. Ranitidine +/- metoclopramide (an anti-emetic that increases gastric emptying).

- Pregnant women lying flat for a Caesarean section are at risk of Mendelson’s syndrome (aspiration of gastric contents into the lung), leading to a chemical pneumonitis. This is because of pressure applied by the gravid uterus on the gastric contents.

- A risk score for venous thromboembolism (VTE) should be calculated for each woman.

- Anti-thromboembolic stockings +/- low molecular weight heparin should be prescribed as appropriate.

Anaesthesia

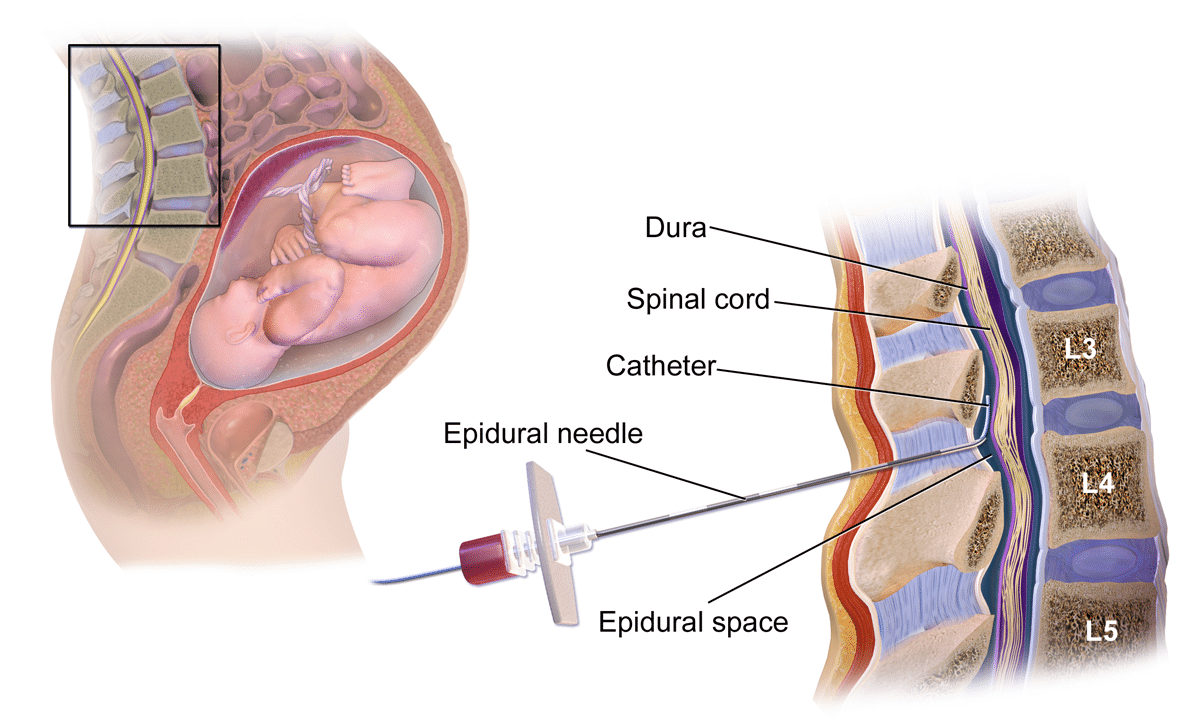

The majority of Caesarean sections are performed under regional anaesthetic – this is usually a ‘topped-up’ epidural or a spinal anaesthetic.

Sometimes a general anaesthetic is required. The can be because of a maternal contraindication to regional anaesthetic, failure of reginal anaesthesia to achieve the required block, or more commonly because of concerns about fetal wellbeing and the need to expedite delivery as soon as possible (often the case for Category 1 sections).

Fig 2 – Epidural anaesthesia is often used in elective Caesarean section.

Operative Procedure

The woman is positioned with a left lateral tilt of 15° – to reduce the risk of supine hypotension due to aortocaval compression.

An indwelling Foley’s catheter is inserted when the anaesthetic is ready, to drain the bladder and to reduce the risk of bladder injury during the procedure.

The skin is then prepared using an antiseptic solution and antibiotics are administered just prior to the ‘knife to skin’ incision.

There are multiple ways to perform a Caesarean, but what follows is a standard technique:

- Skin incision is usually with either a Pfannenstiel or Joel-Cohen – these are both transverse lower abdominal skin incisions.

- Sharp or blunt dissection into the abdomen is made through several layers:

- The skin,

- Camper’s fascia (superficial fatty layer of subcutaneous tissue)

- Scarpa’s fascia, (deep membranous layer of subcutaneous tissue)

- Rectus sheath, (anterior and posterior leaves laterally, that merge medially)

- Rectus muscle,

- Abdominal peritoneum (parietal)

- This reveals the gravid uterus.

- The visceral peritoneum covering the lower segment of the uterus is then incised and pushed down to reflect the bladder, which is retracted by the Doyen retractor.

- Uterine incision is made on the lower uterine segment beneath the line of peritoneal reflection. This is a transverse curvilinear incision which is digitally extended. The baby is then delivered cephalic/breech with fundal pressure from the assistant.

- De Lee’s incision (lower vertical) may be required if the lower uterine incision is poorly formed (rare).

- Oxytocin 5 units is given intravenously by the anaesthetist to aid delivery of the placenta by controlled cord traction by the surgeon.

- The uterine cavity is ensured empty, then closed with two layers. The rectus sheath is then closed and then the skin (either with continuous/interrupted sutures or staples).

Post-Operative

After the Caesarean section, observations are recorded on an early warning score chart, and lochia (per vaginal blood loss post delivery) is monitored.

Early mobilisation, eating and drinking and removal of catheter is encouraged to enhance recovery.

Vaginal Birth After Caesarean Section (VBAC)

In women who have had one Caesarean section, any subsequent pregnancies should be counselled regarding the risks of vaginal birth:

- A planned VBAC is associated with a one in 200 (0.5%) risk of uterine scar rupture.

- The risk of perinatal death is low and comparable to the risk of women labouring with their first child.

- There is a small increased risk of placenta praevia +/- accreta in future pregnancies, and of pelvic adhesions.

- The success rate of planned VBAC is 72–75%, however this is as high as 85-90% in women who have had a previous vaginal delivery.

- All women undergoing VBAC should have continuous electronic fetal monitoring by CTG in labour as a change in fetal heart rate can be the first sign of impending scar rupture.

- Risks of scar rupture is higher in labours that are augmented or induced with prostaglandins or oxytocin.

Complications

A primary Caesarean section carries a reduced risk of perineal trauma and pain, urinary and anal incontinence, uterovaginal prolapse, late stillbirth and early neonatal infections (compared with vaginal birth).

However, it is associated with immediate, intermediate and late complications, which are listed below:

| Stage | Complications |

| Immediate |

|

| Intermediate |

|

| Late |

|