Gestational diabetes is defined as ‘any degree of glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy’.

It is increasing in incidence, with approximately 1 in 5 pregnancies now affected [BMJ, 2014]. Untreated gestational diabetes can have severe untoward effects on the health of the mother and that of the developing fetus.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of gestational diabetes.

Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

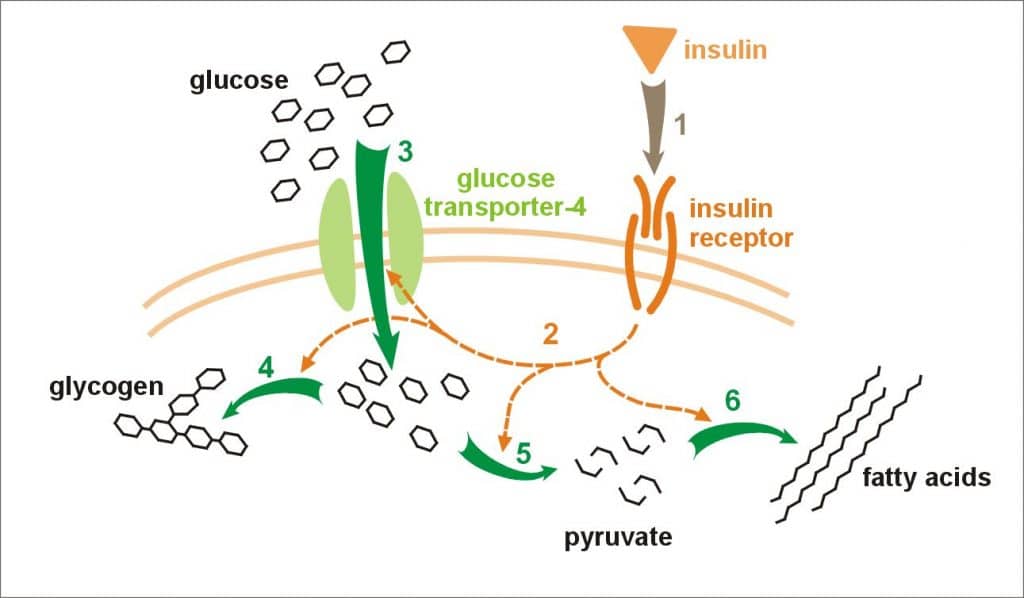

Gestational diabetes occurs when the body is unable to produce enough insulin to meet the needs of the pregnancy. Insulin is a hormone that promotes the uptake of glucose from the blood and its subsequent storage as glycogen.

In pregnancy, there is progressive insulin resistance. This means that a higher volume of insulin is needed in response to a normal level of blood glucose. On average, insulin requirements rise by 30% during pregnancy.

A woman with a borderline pancreatic reserve (Table 1) is unable to respond to the increased insulin requirements, resulting in transient hyperglycaemia. After the pregnancy, insulin resistance falls – and the hyperglycaemia usually resolves.

| Table 1: Risk Factors for Poor Pancreatic Reserve |

| BMI >30 |

| Asian ethnicity |

| Previous gestational diabetes |

| 1st degree relative with diabetes |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome |

| Previous macrosomic baby (>4.5kg) |

Clinical Features

Most women with a borderline pancreatic reserve will be asymptomatic, and will show no signs of gestational diabetes.

If present, the clinical features tend to be the same as other forms of diabetes – i.e. polyuria, polydipsia and fatigue.

Fetal Complications of Gestational Diabetes

In pregnancy, glucose is transported across the placenta, but insulin is not. This can cause fetal hyperglycaemia if there is a high level of glucose in the maternal circulation. Subsequently, the fetus will increase its own insulin levels to compensate; hyperinsulinaemia.

Insulin is a hormone that has a similar structure to growth promotors, and it therefore causes:

- Macrosomia – this can cause complications during labour, such as shoulder dystocia, obstructed/delayed labour, and/or higher rates of instrumental deliveries.

- Organomegaly (particularly cardiomegaly)

- Erythropoiesis (resulting in polycythaemia)

- Polyhydramnios

- Increased rates of pre-term delivery

After delivery, the fetus still has high insulin levels, but no longer receives glucose from its mother. This results in an increased risk of hypoglycaemia – and therefore regular feeding is important.

Additionally, high insulin can cause a reduction in pulmonary phospholipids, which in turn decreases fetal surfactant production. Surfactant acts to reduce the surface tension in alveoli (thus aiding gas exchange), and these babies are at risk of transient tachypnoea of the newborn.

Investigations

The main investigation for gestational diabetes is the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). In this test, a fasting plasma glucose is measured, then a 75g glucose drink is given – with a repeat plasma glucose measurement after 2 hours.

| GDM is diagnosed if: |

|

In the UK, the oral glucose tolerance test is offered at:

- Booking – if previous gestational diabetes.

- 24 – 28 weeks’ gestation – if risk factors are present (Table 1), or in cases of previous gestational diabetes.

- Any point during pregnancy – if 2+ glycosuria on one occasion, or 1+ on two occasions. Alternatively, pre- and postprandial blood sugar monitoring can be performed.

Management

The aim of treatment is to provide good glycaemic control for the duration of the pregnancy. Lifestyle advice should be given regarding diet and exercise – as this alone can sometimes be sufficient. Capillary glucose measurements should be taken four times a day.

The medical management of gestational diabetes involves careful monitoring and control of blood glucose. The medications used to reduce blood glucose include:

- Metformin – suitable in pregnancy and breast feeding.

- Glibenclamide – used if metformin is not tolerated (often due to GI side effects) and insulin has been declined.

- Insulin

- Consider starting at diagnosis if the fasting glucose >7.0mmol/L.

- Or introduce later in pregnancy if

- (i) pre meal glucose > 6.0mmol/L

- (ii) post meal glucose >7.5mmol/L

- (iii) fetal AC (abdominal circumference) >95th centile

In the UK, the obstetric care of any patient with gestational diabetes is consultant-led throughout the pregnancy. Additional growth scans should be performed at 28, 32 and 36 weeks, to monitor for the complications of gestational diabetes (e.g accelerating or large growth, polyhydramnios).

The aim should be to deliver at 37 to 38 weeks if they are on treatment. They would be advised to consider delivery (induction of labour or caesarean section) before 40 weeks and 6 days if there is gestational diabetes managed by diet.

Fig 2 – Female baby (35.5 weeks gestational age) showing macrosomy, with chubby facies typical of gestational diabetes three days after delivery.

Postnatal Care

All anti-diabetic medication should be stopped immediately after delivery. The blood glucose should be measured before discharge to check that it has returned to normal levels.

Around 6-13 weeks post-partum, a fasting glucose test is recommended. If this is normal, yearly tests should be offered because of the increased risk of developing diabetes in the future (50% of mothers with gestational diabetes will go onto develop Type 2 Diabetes in later life).

In subsequent pregnancies, an OGTT should be offered at booking and at 24 – 28 weeks’ gestation.