Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is a description of excessive menstrual loss which interferes with a woman’s quality of life – either on its own or in combination with other symptoms. The definition of ‘excessive’ is set by the woman who presents with the problem.

It is said to affect 3% of women, with those aged 40–51 years most likely to present to healthcare services. HMB refers to bleeding that is not related to pregnancy, and only occurs during the woman’s reproductive years (i.e. not post-menopausal bleeding).

The majority of HMB cases (40-60%) cannot be attributed to any uterine, endocrine, haematological or infective pathology after investigation. These cases were formally referred to as ‘Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding’ as a diagnosis of exclusion – however the term abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is now used.

This article will look at the background of heavy menstrual bleeding, and focus on its investigation and treatment where other pathology has been excluded.

Aetiology & Pathophysiology

FIGO (International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics) have produced a useful mnemonic by which to classify the causes of heavy menstrual bleeding.

The PALM-COEIN system divides the causes into structural (‘PALM’) and non-structural (‘COEIN’):

| PALM: Structural Causes | COEIN: Nonstructural Causes |

| Polyp

Adenomyosis Leiomyoma (Fibroid) Malignancy & hyperplasia |

Coagulopathy

Ovulatory dysfunction Endometrial Iatrogenic Not yet classified |

Risk Factors

The two main risk factors for heavy menstrual bleeding are age (more likely at menarche and approaching the menopause), and obesity.

There are also other risk factors that relate to the specific causes of HMB. One example would be previous caesarean section – as a risk factor for adenomyosis.

Clinical Features

The main features of heavy menstrual bleeding are:

- Bleeding during menstruation deemed to be excessive for the individual woman.

- Fatigue.

- Shortness of breath (if associated anaemia).

A menstrual cycle history should be taken. Inquire about smear history, contraception, medical history and medications – including those taken in an attempt to reduce menstrual bleeding.

Examination of the patient should include a general observation, abdominal palpation, speculum and bimanual examination. Assess for:

- Pallor (anaemia)

- Palpable uterus or pelvic mass

- Try to ascertain if the uterus is smooth or irregular (fibroids)

- A tender uterus or cervical excitation point toward adenomyosis/endometriosis

- Inflamed cervix/cervical polyp/cervical tumour

- Vaginal tumour

Menstrual History

A menstrual cycle history is a key part of the assessment of a woman with heavy menstrual bleeding. It has the following components:

- Frequency – average 28 days

- <24 days Frequent, >38 days Infrequent

- Duration – average 5 days

- >8 days Prolonged, <4.5 days shortened

- Volume – average 40ml menstrual blood loss over course of menses

- >80ml heavy (Hb and Ferritin affected), <5ml Light

- Women may describe ‘flooding’ and clots passed

- Date of last menstrual period (LMP)

Differential Diagnosis

There are numerous differential diagnoses for heavy menstrual bleeding. They are listed with their salient features below:

- Pregnancy:

- A urine pregnancy test is a quick, simple and very important investigation.

- Vaginal bleeding in a pregnant woman may indicate miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy.

- Endometrial or cervical polyps:

- Can also cause intermenstrual or post-coital bleeding.

- They are generally not associated with dysmenorrhoea (painful periods).

-

Adenomyosis:

- Is associated with dysmenorrhoea.

- A bulky uterus can be found on examination.

- Fibroids:

- There may be a history of pressure symptoms (e.g. urinary frequency).

- A bulky uterus can be found on examination.

- Malignancy or endometrial hyperplasia:

- This includes bleeding from vaginal or cervical malignancies, or that provoked by ovarian tumours

- Coagulopathy:

- Von Willebrand’s disease is the most common coagulopathy to cause heavy menstrual bleeding.

- The suggestive features in the history include; HMB since menarche; history of post-partum haemorrhage, surgical related bleeding or dental related bleeding; easy bruising/epistaxis; bleeding gums; family history of bleeding disorder.

- Also consider anticoagulant use e.g warfarin.

- Ovarian dysfunction:

- The two most common causes of ovarian dysfunction are polycystic ovary syndrome and hypothyroidism.

- Iatrogenic causes:

- E.g. contraceptive hormones, copper IUD.

- Endometriosis:

- This represents <5% of all heavy menstrual bleeding cases.

Investigations

All women of reproductive age should have a urine pregnancy test performed. Investigations should be tailored to the specific clinical features, but a generic outline would involve a structured approach as discussed below:

Blood Tests

- Full blood count

- Anaemia tends to present after menstrual blood loss of 120ml.

- Thyroid function test

- If other signs and symptoms of underactive thyroid.

- Other hormone testing

- Not routine but considered if other clinical features e.g. suspicion of Polycystic ovary syndrome.

- Coagulation screen + test for Von Willebrand’s

- If suspicion of clotting disorder on history taking.

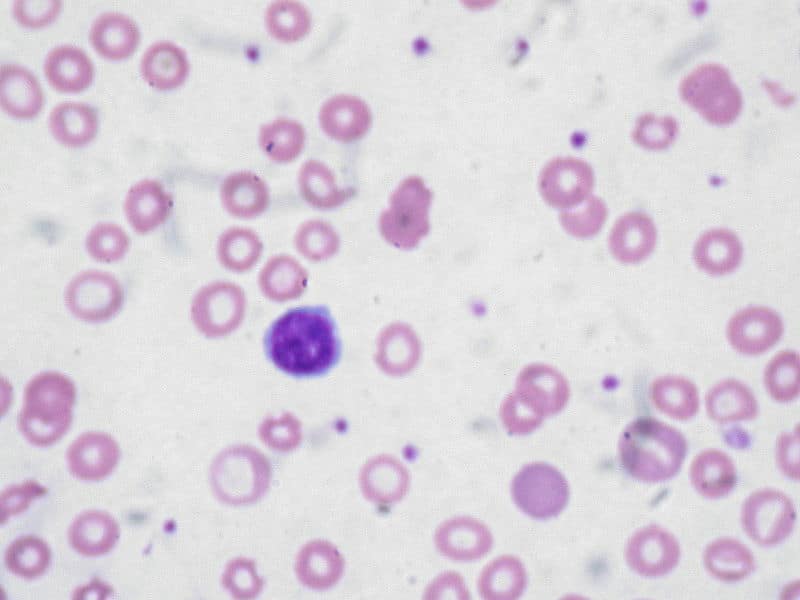

Fig 2 – Iron deficiency anaemia is a common feature of heavy menstrual bleeding. It typically produces a microcytic anaemia.

Imaging, Histology and Microbiology

- Ultrasound pelvis

- Transvaginal US is most clinically useful for assessing the endometrium and ovaries.

- It should be considered if the uterus or a pelvic mass is palpable on examination, or if pharmacological treatment has failed.

- Cervical smear

- No need to repeat if up to date.

- High vaginal and endocervical swabs for infection.

- Pipelle endometrial biopsy:

- Indications for biopsy include persistent intermenstrual bleeding, >45 years old, and/or failure of pharmacological treatment.

- Hysteroscopy and endometrial biopsy:

- Typically performed when ultrasound identifies pathology, or is inconclusive.

Management

When considering management options, discuss with the patient and consider the impact on her fertility. The aim of management is to improve the woman’s quality of life, rather than a specific reduction in the volume of blood she loses.

Pharmacological

In the UK, where there is no suspicion of pathology, there is a 3 tiered approach to pharmacological management:

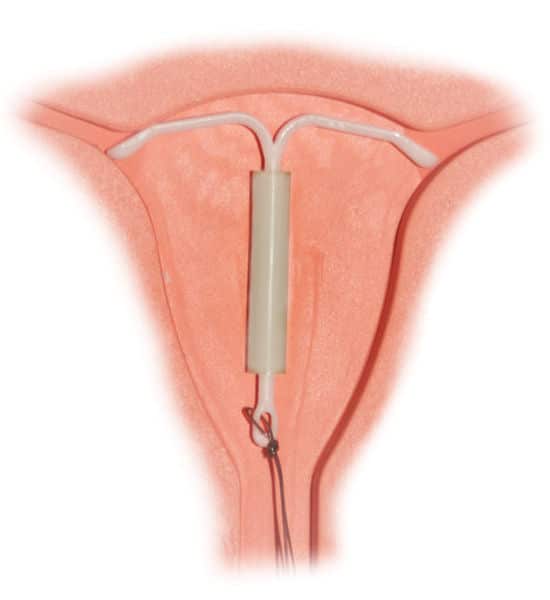

- Levonorgestral-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS):

- Also acts as a contraceptive.

- Is licensed for 5 years treatment.

- Thins endometrium and can shrink fibroids.

- Tranexamic acid, mefanamic acid or combined oral contraceptive pill:

- The choice is dependant on woman’s wishes for fertility.

- Tranexamic acid taken only during menses to reduce bleeding, no effect on fertility.

- Mefanamic acid is an NSAID so also offers analgesia for dysmenorrhoea, taken only during menses, no effect on fertility.

- Progesterone only: oral norethisterone (Taken day 5-26 of cycle), depo or implant:

- Oral norethisterone does not work as a contraceptive when taken in this manner, therefore other contraceptive methods should be applied.

- Depo and implant progesterone are long active reversible contraceptives.

Fig 3 – The mirena intrauterine system, part of the pharamacological management of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Surgical

There are two main surgical treatment options for heavy menstrual bleeding; (i) Endometrial ablation and (ii) Hysterectomy.

Note: There are two additional surgical treatments – myomectomy and uterine artery embolisation. However, they are only used to treat HMB that is caused by fibroids.

Endometrial ablation is where the endometrial lining of the uterus is obliterated. It is suitable for women who no longer wish to conceive (although they will need to continue using contraception), and can reduce HMB by up to 80%. Ablation can be performed in the outpatient setting with local anaesthetic.

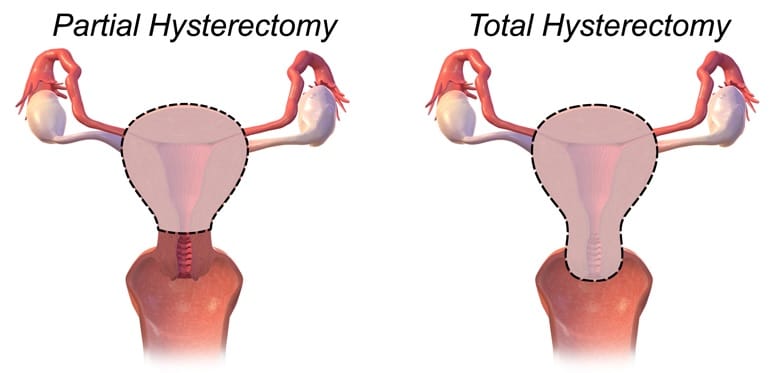

The only definitive treatment for HMB is hysterectomy. It offers amenorrhoea and an end to fertility. There are two main types performed:

- Subtotal (partial) – removal of uterus, but not cervix.

- Total – removal of cervix with uterus.

In both cases, the ovaries are not removed (unless abnormal). Hysterectomy can be performed through an abdominal incision or via the vagina.

Fig 4 – Partial (subtotal) and total hysterectomy.

Summary

- Heavy menstrual bleeding is defined by the woman presenting with the problem

- Multiple structural and non-structural causes, however 40-60% of cases not attributed to any of these

- Three tiered pharmacological approach to treatment is the first line

- The woman’s fertility must be considered with all treatment approaches

- Surgical options for treatment include ablation and hysterectomy