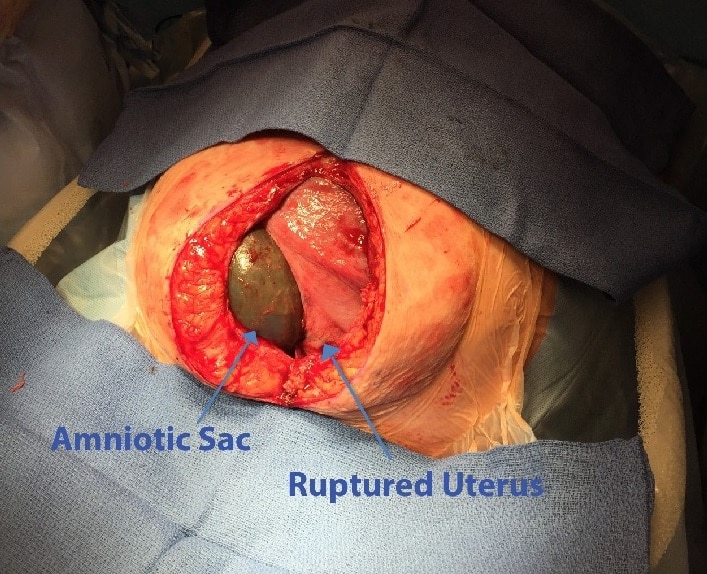

Uterine rupture refers to a full-thickness disruption of the uterine muscle and overlying serosa. It typically occurs during labour, and can extend to affect the bladder or broad ligament.

There are two main types:

- Incomplete – where the peritoneum overlying the uterus is intact. In this case, the uterine contents remain within the uterus.

- Complete – the peritoneum is also torn, and the uterine contents can escape into the peritoneal cavity.

It is a rare complication, but one that is associated with significant maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of uterine rupture.

Risk Factors

The risk factors for uterine rupture are generally those that make the uterus inherently weaker:

- Previous caesarean section – this is the greatest risk factor for uterine rupture.

- Classical (vertical) incisions carry the highest risk.

- Previous uterine surgery – such as myomectomy.

- Induction – (particularly with prostaglandins) or augmentation of labour.

- Obstruction of labour – this is an important risk factor to consider in developing countries.

- Multiple pregnancy.

- Multiparity.

Clinical Features

The initial clinical features of uterine rupture are non-specific, which makes diagnosis and prompt management difficult.

The most common presenting symptom is sudden severe abdominal pain, which persists between contractions. The patient may also experience shoulder-tip pain (from diaphragmatic irritation) and/or vaginal bleeding.

On examination, there may be regression of the presenting part, with abdominal palpation revealing scar tenderness and palpable fetal parts. Significant haemorrhage can produce signs of hypovolaemic shock; such as tachycardia and hypotension.

Fetal monitoring may reveal fetal distress or absent heart sounds.

Differential Diagnoses

The main differential diagnoses to consider are:

- Placental abruption – presents with abdominal pain +/- vaginal bleeding. The uterus is often described ‘woody’ and tense on palpation.

- Placenta praevia – typically causes a painless vaginal bleeding.

- Vasa praevia – characterised by a triad of ruptured membranes, painless vaginal bleeding, and fetal bradycardia.

Investigations

In women at risk of uterine rupture, intrapartum monitoring with cardiotocography is vital. Changes in fetal heart rate pattern (such as recurrent or late decelerations) and prolonged fetal bradycardia are early indicators for uterine rupture.

In many cases, a pathological CTG prompts an emergency section – with uterine rupture noted intra-operatively. Maternal haematuria may also be present on catheterisation.

If there is a suspicion of uterine rupture in the pre-labour setting, ultrasound can be used for diagnosis. Features include abnormal fetal lie or presentation, haemoperitoneum and absent uterine wall.

Management

Uterine rupture is an obstetric emergency. Therefore, it is vital to first undertake an A-E approach, and call the appropriate staff – including senior obstetricians, midwives and anaesthetists, and, where appropriate, invoke the Massive Obstetric Haemorrhage protocol.

Resuscitation

- Protect airway (may lose it with reduced levels of consciousness)

- 15L of 100% oxygen through a non-rebreathe mask

- Assess circulatory compromise (Cap refill, HR, BP, ECG)

- Insert two large bore (14G) cannulas and take blood samples

- Start circulatory resuscitation. Give cross-matched blood as soon as it is available, until then give up to 2L of warmed crystalloid and 1-2L of warmed colloids, then transfuse O negative or uncross matched group specific blood.

- Additional blood products may be required, such as fresh frozen plasma, platelets and/or fibrinogen.

- Monitor patient’s GCS

- Expose patient to identify any other bleeding sources

Surgical Management

The fetus is delivered by Caesarean section, and the uterus is either repaired or removed (hysterectomy). In the UK, guidelines suggest that the decision-incision interval in operative intervention should be less than 30 minutes.