Secondary postpartum haemorrhage is defined as excessive vaginal bleeding in the period from 24 hours after delivery to twelve weeks postpartum.

The overall incidence of secondary postpartum haemorrhage in the developed world has been reported as 0.47% – 1.44%.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of secondary post-partum haemorrhage.

Aetiology & Risk Factors

The main causes of secondary post-partum haemorrhage are:

- Uterine infection – (known as endometritis).

- Risk factors include Caesarean section, premature rupture of membranes and long labour.

- Retained placental fragments or tissue

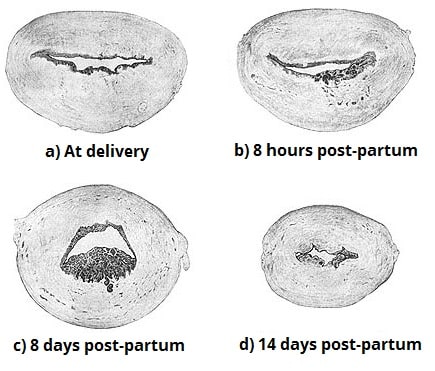

- Abnormal involution of the placental site (inadequate closure and sloughing of the spiral arteries at the placental attachment site).

- Trophoblastic disease (very rare).

A personal history of secondary PPH is a strong predictive factor; it has a recurrence rate of 20–25%.

Clinical Features

The main symptom of secondary post-partum haemorrhage is excessive vaginal bleeding. In contrast to primary PPH (an acute condition requiring immediate management), the bleeding in secondary post-partum haemorrhage is usually not as severe.

The patient may complain of spotting on-and-off for days after her delivery, with an occasional gush of fresh blood. However, approximately 10% of cases will present with massive haemorrhage – and this can quickly lead to hypovolemic shock.

Additional clinical features will depend on the underlying cause. For example, women with endometritis may also present with fever/rigors, lower abdominal pain or foul smelling lochia (the normal discharge from the uterus following childbirth).

On abdominal examination, the patient may complain of lower abdominal tenderness (usually a sign of endometritis), or the uterus may still be high (sign of retained placenta). Speculum examination is important in order to assess the amount of bleeding, and a high vaginal swab should be taken at the same time.

Investigations

If the patient is haemodynamically unstable or is bleeding heavily, then call for help and follow the resuscitation algorithm. Resuscitation should be commenced prior to establishing a cause, and senior staff should be involved at the earliest opportunity.

Laboratory Tests

The appropriate laboratory tests include:

- Full Blood Count

- Urea and Electrolytes

- C-Reactive Protein

- Coagulation profile

- Group and Save sample

- Blood cultures (if the patient is pyrexic)

Imaging Tests

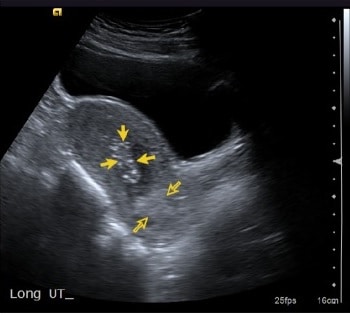

A pelvic ultrasound scan can assist in the diagnosis of retained placental tissue.

Note: The over-diagnosis of retained placental tissue on ultrasound can lead to unnecessary surgical intervention. However, ultrasound does have a good negative predictive value, and is therefore particularly helpful in excluding a diagnosis of retained placental tissue.

Management

The mainstay of treatment in secondary PPH is with antibiotics and uterotonics:

- Antibiotics – usually a combination of ampicillin (clindamycin if penicillin allergic) and metronidazole.

- Gentamicin should be added to the above combination in cases of endomyometritis (tender uterus) or overt sepsis.

- Note: antibiotic regimes will differ according to local hospital Trust anti-microbial guidelines.

- Uterotonics – examples include syntocinon (oxytocin), syntometrine (oxytocin+ergometrine), carboprost (prostaglandin F2) and misoprostol (Prostaglandin E1).

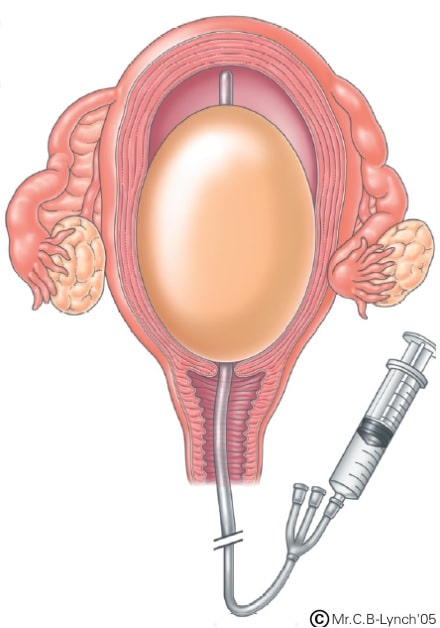

Surgical measures should be undertaken if there is excessive or continuing bleeding (irrespective of ultrasound findings). In continuing haemorrhage, insertion of a balloon catheter into the uterus may be effective.

In the case of massive secondary PPH, management includes four components, which should be undertaken simultaneously. These are: (i) communication, (ii) resuscitation, (iii) monitoring and investigation (as described in the investigation section) and (iv) arresting the bleeding (with uterotonics/surgical measures, depending on the suspected cause).

Note: Any surgical evacuation of retained products of conception carries a high risk of uterine perforation (as the uterus is softer and thinner post-partum). It should involve a senior obstetrician in the planning and delivery of surgery.

Fig 3 – Balloon Tamponade, a surgical intervention of severe bleeding in secondary post-partum haemorrhage.

Summary

- Secondary PPH may occur between 24hrs up to twelve weeks postpartum.

- It may be associated with infection, retained placental tissue or abnormal involution of the placental site.

- A pelvic USS should be arranged in order to rule out the possibility of retained placental tissue. However, it is often difficult to differentiate between blood clots and retained tissue.

- The mainstay of management is antibiotics and uterotonics.

- Surgical measures should be undertaken if there is excessive or continuing bleeding, irrespective of ultrasound findings.