Vulvovaginal candidiasis is a fungal infection of the lower female reproductive tract, commonly known as “thrush” or a “yeast infection”. The prevalence of vulvovaginal candidiasis peaks in women aged 20-40 and it is a highly common infection that most of the female population will experience on at least one occasion.

It is therefore important to consider the pathophysiology, diagnosis and clinical management of this infection, all of which will be discussed in this article.

Pathophysiology

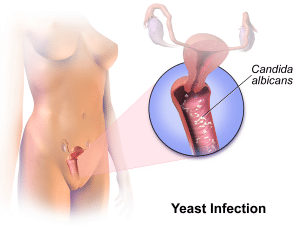

The pathogen in 90% of candidiasis cases is the commensal organism Candida albicans. This particular yeast-like fungus characteristically replicates by budding and can be found as part of the body’s normal flora in the gastro-intestinal tract. Due to this, there are also instances of oral candidiasis in both men and women. For the purposes of this article however we will be focusing on candida infection of the female lower genital tract.

Candidiasis infections have been traditionally thought of as opportunistic infections. These infections exploit opportunities such as weakened host defences e.g. a compromised immune system or altered micro biota.

However, a new line of thinking proposes that symptomatic candidiasis infections may also be as a result of a hypersensitivity reaction to the commensal organism Candida albicans, with genetics and oestrogen levels also thought to play a role.

Note up to 20% of women may carry candida asymptomatically and do not require treatment. Also, a positive Candida swab does not necessarily mean that Candida is the cause of the woman’s symptoms.

Figure 1 – Commensal organism Candida albicans affecting the lower female reproductive tract

Risk Factors

- Pregnancy

- Diabetes

- Use of broad spectrum antibiotics

- This can alter the normal vaginal micro-biota, allowing candida the opportunity to flourish and grow.

- Use of corticosteroids

- The immunosuppressive action of corticosteroids can allow commensal candida the opportunity to thrive excessively.

- Immunosuppression or compromised immune system

- For example in HIV or cancer patients. May be associated with a more advanced and potentially life-threatening candida infection, or recurrent candidiasis which is difficult to treat.

Clinical Features

Symptoms

Taking an appropriate history is essential. Symptoms that patients may complain of that are indicative of candidiasis include:

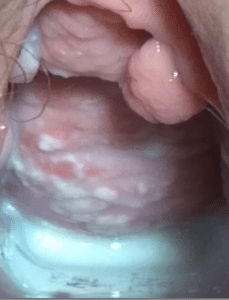

Figure 2 – Speculum exam showing a white curd-like plaque on the anterior vaginal wall.

- Pruritus vulvae

- Itchiness of the vulva – which can extend to the perineal region in some women. This is usually a dominant symptom.

- Vaginal discharge

- Usually white, curd-like and non-offensive in candida infections.

- Dysuria (superficial dysuria)

Signs

Signs on examination may reveal:

- Erythema and swelling of the vulva

- Satellite lesions

- Red, pustular lesions with superficial white/creamy pseudomembranous plaques that can be scraped off.

- Curd-like discharge in vagina

Differential Diagnosis

Other infectious causes of the reported symptoms must be considered and eliminated. Common infectious differentials for candidiasis are:

- Bacterial vaginosis – In this case there is usually no soreness or irritation, however white discharge is present. The discharge can be offensive due to the bacterial cause of infection. Smear, microscopy and culture of discharge can be used to exclude and differentiate between diagnoses.

- Trichomonas vaginalis – The pathogen responsible for this infection is a flagellated protozoan. Patients may complain of vaginal soreness, pain when passing urine and a change in vaginal discharge. Vaginal discharge may change in a variety of ways, it can become thicker or thinner, frothy or yellow. Trichomonas vaginalis is treated with antibiotics rather than antifungals.

- Urinary Tract Infection – This infection also presents with dysuria and must be excluded.

Non-infectious causes should also be considered:

- Contact dermatitis – To gather more information to exclude or include this as a diagnosis it may be useful to enquire about changes in hygiene products.

- Eczema and psoriasis – Skin lesions and pruritus vulvae may be as a result of eczema and/or psoriasis, more information to indicate these differential diagnoses can be obtained through a detailed history.

It is also important to rule out diabetes mellitus as an underlying disorder. The likelihood of underlying diabetes can be evaluated by asking about symptoms of diabetes (polyuria, polydipsia and weight loss) in the history.

Investigations

No investigations are necessary if the history indicates an acute uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidiasis – defined as a sporadic case with mild to moderate symptoms likely to be due to Candida albicans and not associated with risk factors (such as pregnancy, diabetes and compromised immunity). However, measuring vaginal pH is recommended if the woman is examined.

In candidiasis cases that are not classified as ‘uncomplicated’ (for example, recurrent infection) a vaginal smear and microscopic investigation of the sample should be carried out. The presence of spores and mycelia are indicative of candida infection (although it is important to bear in mind that they may also be present in non-symptomatic women due to Candida albicans being a commensal organism).

Management

This article will be discussing the treatment of uncomplicated vulvovaginal candidiasis.

- Initial course of an intravaginal antifungal, such as clotrimazole or fenticonazole – usually inserted into the vagina via applicator.By TeachMeSeries Ltd (2024)

Figure 3 – For vulvovaginal candidiasis, clomitrazole is inserted into the vagina.

- Oral antifungal, such as fluconazole or itraconazole can also be prescribed as an alternative to the intravaginal treatment.

- Topical imidazole can also be prescribed in conjunction with the oral or intravaginal antifungal to address vulval symptoms.

Both intravaginal clotrimazole and oral fluconazole can be purchased over-the-counter. Topical azoles are usually oil-based therefore may weaken latex condoms.

Full management recommendations cane be accessed here (NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries).

If symptoms have not subsided in 7-14 days, advise the patient to return to seek medical attention. In cases of failure to clear the infection:

- Consider alternative diagnoses by measuring vaginal pH and taking a vaginal swab for microscopy and culture.

- Consider predisposing risk factors and attempt to address them. For example, in the case of a diabetic woman, better control of her diabetes could improve the treatment of vaginal candidiasis or make cases less frequent.

- Consider the patient’s concordance with the medication and reasons why concordance may have been poor. Also assess whether medication has been administered correctly.

If treatment continues to fail and symptoms persist, or if non-albicans Candida species has been identified, referral to a specialist is recommended.

It is worth discussing with the patient ways to best avoid recurrence of candidiasis. Advise using soap substitutes and avoid cleaning the vaginal area more than once a day, avoid potential irritants e.g. shower gels, vaginal deodorants, douches and avoid wearing tight fitting underwear/tights.

Candidiasis in Pregnancy

Oestrogen levels are thought to have an impact on the likelihood of developing a candidiasis infection by stimulating increased glycogen production, this provides a more favourable environment for microorganisms to thrive. It is also thought that oestrogen may have a direct influence on the candida organism by promoting its growth and encouraging it to ‘stick’ to the walls of the vagina. Increased levels of oestrogen in pregnancy could mean that candida infections are more likely in some women.

Management of candidiasis in pregnancy:

- Treat infection with intravaginal antifungal (e.g. clotrimazole)

- Do not give oral antifungals such as fluconazole and itraconazole

- Treat vulval symptoms with topical antifungal

- Advise the patient to be careful to avoid physical damage when inserting intravaginal treatment applicator

- When taking history note of any evidence of sexually transmitted diseases, as many STIs can affect the pregnancy. Refer to GUM (genito-urinary medicine) clinic if STI is suspected.

- Advise patient to return if symptoms have not resolved within 7-14 days

Further information for management of candidiasis in pregnancy can be found here.