An ovarian cyst is a fluid filled sac within the ovary. They are common; especially in the premenopausal patients where benign, physiological cysts predominate throughout the menstrual cycle.

As a general rule, these women presenting with small cysts should not raise concern unless symptomatic and often resolution is confirmed on scanning a few weeks down the line (often by departmental protocols with a scan at 12 weeks, or three menstrual cycles).

The obvious concern of patients with ovarian masses is the presence of malignancy. The risk of malignancy index (RMI) is a tool used in practice to determine the likelihood of this which allows triage and referral to a cancer centre for treatment as indicated.

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death from gynaecological malignancy in the UK. It accounts for roughly 2 percent of total cancer cases with over half of cases diagnosed in women aged 65 and over.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of ovarian cysts and tumours

Risk Factors

Ovarian cancers are believed to derive from surface epithelial irritation during ovulation. Therefore, the more ovulations that take place, the increased risk of developing malignancy:

| Risk Factors | Protective Factors |

|

|

There is also a genetic component to ovarian cancer, with family history being particularly important. Several inherited genetic mutations are important to recognise:

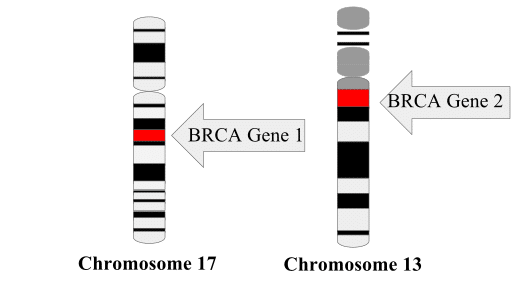

- BRCA1 & 2 – these mutations increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancers. Ovarian cancer risk is as much as 46% at age 70 in BRCA1 positive families and 12% in BRCA2. Prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy can be performed in these patients however this does not completely eradicate the risk of developing malignancy.

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch II Syndrome) – this is a rare syndrome with an associated increased risk of developing colorectal and endometrial cancers. It also confers a lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer quoted at around 12%.

Fig 1 – Presence of the BRCA1 or 2 genes greatly increases the risk of ovarian cancer.

Risk of Malignancy Index

The risk of malignancy index (RMI) can be used as a risk stratification tool in those patients with suspected ovarian cancer. It is calculated as:

RMI = U x M x CA125

| Factor | 0 Points | 1 Point | 3 Points |

| Menopausal status (M) | premenopausal | postmenopausal | |

Ultrasound score (U)

|

No features from list |

1 feature from list |

2 or more features from list |

| CA125 | Cancer Antigen 125. Measured from a blood test, giving a value in units/ml | ||

So for a postmenopausal patient with a CA125 of 100 and bilateral lesions with solid areas identified on ultrasound her score would be 3 x 3 x 100 = 900.

Patients with a RMI >250 should be referred to a specialist gynaecologist.

Clinical Features

The clinical features of ovarian cysts and tumours can vary depending on the size and type of pathology present. Common presentations include:

- Incidental and asymptomatic – found on scanning for other reasons e.g. pregnancy.

- Chronic pain – may develop secondary to pressure on the bladder or bowel also causing frequency or constipation.

- It may also manifest as dyspareunia or cyclical pain in those patients with endometriosis who have developed chocolate cysts.

- Acute pain – these patients may have bleeding into the cyst, rupture or torsion.

- Bleeding per vagina.

When taking a history from patients it is important to bear in mind that the presentation of ovarian cancer is often vague causing a delay in diagnosis and presentation to specialists with advanced disease. Therefore, never ignore a postmenopausal patient with nonspecific gynaecological or gastrointestinal symptoms. Enquire specifically about:

- Bloating

- Change in bowel habit

- Change in urinary frequency

- Weight loss

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Bleeding per vagina

On examination it is important to resuscitate a shocked patient who may have presented with cyst rupture or torsion. Following this, look for abdominal masses arising from the pelvis and ascites. Examine the pelvis for discharge or bleeding, adnexal masses and cervical excitation.

Ovarian Cysts

Classification

Ovarian tumours can be divided into non-neoplastic (no malignant potential) and neoplastic (ability to turn malignant).

- A simple ovarian cyst is one that contains fluid only.

- A complex ovarian cyst is one that is not simple! It can be irregular and can contain solid material, blood or have septations or vascularity.

Below is a table describing a categorisation of benign ovarian cysts.

| Non-Neoplastic |

Functional:

|

Pathological:

|

| Benign Neoplastic |

Epithelial tumours:

|

Benign germ cell tumours:

|

Sex-cord stromal tumours:

|

Management

Premenopausal women:

- CA125 does not need to be undertaken when the diagnosis of a simple ovarian cyst has been made ultrasonographically. The CA125 can be raised by anything that irritates the peritoneum, so in premenopause there are numerous benign triggers for an increase.

- Lactate dehydrogenase, alphafetoprotein and hCG should be measured in all women under 40 due to the possibility of germ cell tumours.

- Rescan a cyst in 6 weeks. If it is persistent then monitor with ultrasound an CA125 3-6 monthly and calculate RMI.

- If persistent or over 5cm consider laparoscopic cystectomy or oophorectomy.

Postmenopausal women:

- Low RMI (less than 25): follow up for 1 year with ultrasound and CA125 if less than 5cm.

- Moderate RMI (25-250): bilateral oophorectomy and if malignancy found then staging is required (with completion surgery of hysterectomy, omentectomy +/- lymphadenectomy).

- High RMI (over 250): referral for staging laparotomy

Ovarian Cancer

The clinical features of ovarian cancer are non-specific, and most patients present with late-stage disease. They are most often of the epithelial subtype:

- Serous cystadenocarcinoma – characterised by Psammoma bodies.

- Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma – characterised by mucin vacuoles.

All patients with suspected ovarian cancer should have basic blood tests included FBC, U&E, LFT and albumin. In the UK, NICE recommends abdominal and pelvic ultrasound for pelvic masses, from which the RMI can be calculated.

In cases of confirmed cancer, chest x-ray and CT abdomen/pelvis should be undertaken for staging and pre-operative purposes.

Management

- Surgery – staging laparotomy for those with a high RMI with attempt to debulk the tumour.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy – recommended for all patients apart from those with early, low grade disease and uses platinum based compounds.

- Follow up – involves clinical examination and monitoring of CA125 level for 5 years with intervals between visits becoming further apart according to risk of recurrence.

Summary

- Benign ovarian tumours are extremely common particularly in young patients.

- Despite this, they can cause problems due to bleeding, torsion and rupture.

- The risk of ovarian cancer is related to the number of ovulations occurring in reproductive life.

- Be aware of the difficulty in diagnosing ovarian cancer and exercise caution when dealing with postmenopausal women with non-specific presentations.

- The risk of malignancy index is useful in identifying those patients at risk of having ovarian cancer.