Genital warts are benign epithelial or mucosal outgrowths caused by the DNA human papilloma virus (HPV). HPV is the most prevalent viral sexually transmitted infection however rates are expected to decrease following the introduction of the HPV vaccine.

In this article we shall cover the pathophysiology of HPV, its clinical features, investigations and the treatments available.

Pathophysiology

There are over 100 types of the human papilloma virus, responsible for different types of warts. More than 40 types of HPV have been associated with anogenital warts (condyloma acuminatum) however HPV6 and HPV11 are responsible for roughly 90% of cases.

Infections of HPV resulting in genital warts are primarily spread through skin-to-skin contact during vaginal and anal sexual intercourse, however penetrative sex is not necessary for transmission. It is important to note that condoms do not fully protect against HPV as not all skin is covered e.g. the inner thighs. In rare cases it can be passed on from the hand to genitals, during oral sex and to the neonate during delivery.

Following infection, the virus penetrates the epithelial barrier and infects basal keratinocytes. Within the keratinocyte the virus replicates resulting in multiplication of the keratinocyte and this rapid growth manifests as lesions.

Oncogenic HPV

There are certain types of HPV that are high risk and may result in pre-cancerous lesions. Persistent infection with these high risk types can lead to cancer of the vulva, vagina, cervix and anus.

Nearly all cervical cancer cases are related to HPV, with HPV16 and HPV18 accounting for 70% of cases. This is usually initially picked up when a woman has abnormal test results indicative of abnormal cell changes following cervical screening. HPV 6 and 11 are low risk types and are not associated with cancer.

Risk Factors

The following are risk factors typically associated with HPV, some of which are common to many other STIs.

- Early age at first sexual intercourse

- Multiple partners

- Immunosuppression

- Smoking

- Diabetes associated with persistence of warts

Clinical Features

Most HPV infections are asymptomatic, do not result in lesions and resolve spontaneously. Symptomatic men and women may present with warts affecting the penis, scrotum, vulva, inside the vagina, cervix, perianal skin or inside the anus. This can be weeks, months or years after the initial infection. Lesions are usually painless, fleshy growths that can be soft or hard and can be singular or multiple. Occasionally warts may cause irritation or become inflamed.

HPV types related to anogenital lesions can also be responsible for extra-genital lesions affecting the oral cavity, larynx, conjunctivae and the nasal cavity.

Differential Diagnoses

- Vestibular papillomatosis: projections of the vestibular epithelium or labia minora (non-viral and not sexually transmitted). Application of acetic acid does not change their colour – HPV lesions turn whitish.

- Molluscum contagiosum: viral infection causing small firm raised papules on the skin.

Although anogenital warts are relatively easy to diagnose via examination, patients should be offered a full STI screen due to the possibility of co-infection and due to the common signs and symptoms of different STIs.

Investigations

Diagnosis is usually made on examination of the genitalia and perianal skin alone, where small lesions may require magnification using a colposcope. Proctoscopy may be necessary if there are warts around the anal margin or if there are symptoms such as irritation and bleeding. Females may also require a vaginal speculum examination to check for internal warts.

Biopsy may be required for atypical lesions and suspected intraepithelial neoplastic lesions.

Management

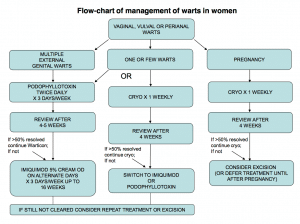

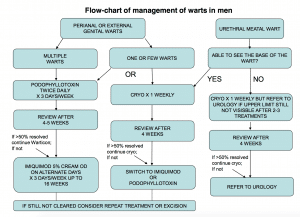

Treatment is not always necessary and lesions will most likely resolve spontaneously over time, particularly in the postpartum period. Treatment for visible lesions may take several months and the choice of treatment depends on the morphology, number and location of the warts.

Topical Treatments:

- Podophyllotoxin: applied twice daily for 3 days followed by 4 days rest (4-5 cycles)

- Clusters of small warts, better for non-keratinised lesions

- Imiquimod: applied 3 times weekly and wash off after 6-10 hours (up to 16 weeks)

- Larger warts, particularly keratinised warts

- Catephen®: applied 3 times daily (up to 16 weeks)

- Not really used in the UK

- Trichloroacetic acid: applied once weekly by a healthcare professional

- Not really used in the UK

Topical treatments may weaken latex condoms. They are also contraindicated in pregnancy and breastfeeding, and may cause local inflammation.

Physical ablation:

- Excision: surgical removal under local anaesthetic

- Pedunculated/large warts or accessible small hard warts

- Cryotherapy: freezing using liquid nitrogen usually repeated weekly (consider alternative treatment if no response after 4 weeks)

- Multiple small warts

- Electrosurgery: excision removes the majority of the wart and then an electric current is passed through a metal loop pressed against the wart to remove any remaining part

- Large warts that have failed to respond to topical treatment

- Laser surgery: a laser is used to burn the warts under local or general anaesthetic.

- Difficult to access warts e.g. inside the anus

A change in therapy is recommended if there is <50% response to treatment after 4-5 weeks (8-12 for Imiquimod).

Fig 2 – BASHH flow-chart for the management of anogenital warts in women.

Fig 3 – BASHH flow-chart for the management of anogenital warts in men.

For detailed management of anogenital warts see the BASHH UK National Guidelines.

Vaccination

In the UK the HPV vaccine is offered to all girls aged 12-13. This was introduced in 2008 and the vaccine originally protected against the high risk HPV types 16 and 18, however since 2012 the vaccine Gardasil® additionally protects against the most common types HPV 6 and 11. The vaccine is most beneficial if administered before first sexual contact. It is argued that only immunising females will not necessarily protect males and herd immunity will not apply to men who have sex with men. In some countries, Gardasil is administered to both males and females.

HPV in Pregnancy

HPV is not associated with miscarriage, premature birth or other pregnancy complications. However, due to the hormonal changes associated with pregnancy, genital warts may multiply or enlarge. Treatment aims to reduce the burden of lesions so that during childbirth the neonate’s exposure is reduced. During pregnancy, podophyllotoxin and imiquimod are not recommended and physical ablation methods are preferred.

The risk of transmission to the neonate during birth is extremely low. If the baby does become infected, the immune system will usually clear the virus however in rare cases the baby may develop respiratory papillomatosis, where genital warts develop in the throat.