Placental abruption is where a part or all of the placenta separates from the wall of the uterus prematurely. It is an important cause of antepartum haemorrhage – vaginal bleeding from week 24 of gestation until delivery.

In this article, we shall look at the pathophysiology, clinical features and management of placental abruption.

Pathophysiology

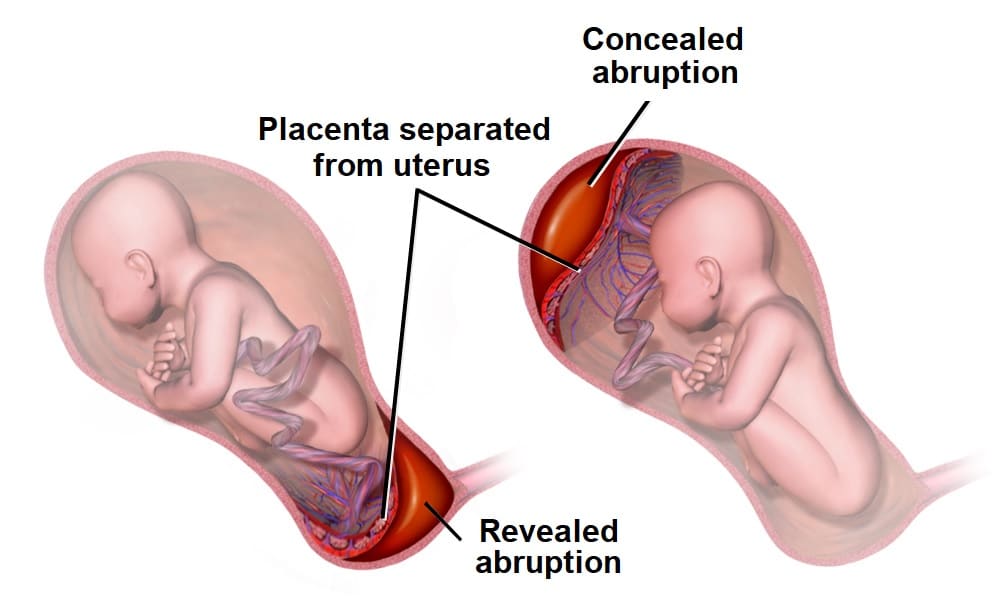

Placental abruption is where a part or all of the placenta separates from the wall of the uterus prematurely.

Abruption is thought to occur following a rupture of the maternal vessels within the basal layer of the endometrium. Blood accumulates and splits the placental attachment from the basal layer. The detached portion of the placenta is unable to function, leading to rapid fetal compromise.

There are two main types of placental abruption:

- Revealed – bleeding tracks down from the site of placental separation and drains through the cervix. This results in vaginal bleeding.

- Concealed – the bleeding remains within the uterus, and typically forms a clot retroplacentally. This bleeding is not visible, but can be severe enough to cause systemic shock.

Risk Factors

The major risk factors for placental abruption include:

- Placental abruption in previous pregnancy (most predictive factor)

- Pre-eclampsia and other hypertensive disorders

- Abnormal lie of the baby e.g. transverse

- Polyhydramnios

- Abdominal trauma

- Smoking or drug use e.g. cocaine

- Bleeding in the first trimester, particularly if a haematoma is seen inside the uterus on a first trimester scan.

- Underlying thrombophilias

- Multiple pregnancy

Clinical Features

Any woman presenting with antepartum haemorrhage should be assessed in a systematic manner (see box below).

Placental abruption typically presents with painful vaginal bleeding (bleeding may not be visible if it is concealed). If the woman is in labour, inquire about pain between contractions.

On examination, the uterus may be woody (tense all of the time) and painful on palpation.

Assessment of Antepartum Haemorrhage

History

The following questions are useful to ask in the assessment of antepartum haemorrhage:

- How much bleeding was there and when did is start?

- Was it fresh red or old brown blood, or was it mixed with mucus?

- Could the waters have broken (membranes ruptured?)

- Was it provoked (post-coital) or not?

- Is there any abdominal pain?

- Are the fetal movements normal?

- Are there any risk factors for abruption? e.g. smoking/drug use/trauma – domestic violence is an important cause.

If the bleed is ongoing, or if there has been a significant vaginal bleed, ABC assessment and resuscitation is vital. If the woman is clinically stable, proceed to examination.

General Examination

On general examination, the following should be assessed:

- Pallor, distress, check capillary refill, are peripheries cool?

- Is the abdomen tender?

- Does the uterus feel ‘woody’ or ‘tense’ (which may indicate placental abruption)?

- Are there palpable contractions?

- Check the lie and presentation of the fetus/fetuses. Ultrasound can be used to help.

- Check fetal wellbeing with a cardiotocograph (CTG) at 26 weeks gestation or above: (otherwise auscultate the fetal heart only).

- Read the hand-held pregnancy notes: are there scan reports? This will be helpful in establishing whether there could be placenta praevia

Assessment of Bleeding

Lastly, the bleeding itself should be assessed:

- Externally e.g. by looking at pads.

- Cusco speculum examination: avoid this until placenta praevia has been excluded by USS.

- Look for whether blood is fresh red or dark. How much blood is there? Are there clots? Are there any cervical lesions? Is there any cervical dilatation, or any chance that the membranes have ruptured?

- Take triple genital swabs to exclude infection if the bleeding is minimal

- Digital vaginal examination: A digital vaginal examination with known placenta praevia should NOT be performed as it could cause massive bleeding.

- In minor bleed, when placenta praevia is excluded, it can help to establish whether the cervix is beginning to dilate.

- Avoid digital VE if the membranes have ruptured.

Differential Diagnoses

Placental abruption is an important cause of antenatal haemorrhage; but it is not the most common. Differential diagnoses to consider include:

- Placenta praevia – where the placenta is fully or partially attached to the lower uterine segment.

- Marginal placental bleed – small, partial abruption of the placenta which is large enough to cause revealed bleeding, but not large enough to cause maternal or fetal compromise.

- Vasa praevia – where fetal blood vessels run near the internal cervical os. It is characterised by a triad of (i) Vaginal bleeding; (ii) Rupture of membranes; and (iii) Fetal compromise.

- The bleeding occurs following membrane rupture when there is rupture of the umbilical cord vessels, leading to loss of fetal blood and rapid deterioration in fetal condition.

- Uterine rupture – a full-thickness disruption of the uterine muscle and overlying serosa. This usually occurs in labour with a history of previous caesarean section or previous uterine surgery such as myomectomy.

- Local genital causes:

- Benign or malignant lesions – e.g. polyps, carcinoma. cervical ectropion (common).

- Infections – e.g. candida, bacterial vaginosis and chlamydia.

Investigations

If major bleeding is suspected, resuscitate and perform investigations simultaneously.

Haematology

- Full blood count – assess any maternal anaemia.

- Clotting profile

- Kleihauer test – if the woman is Rhesus negative (to determine the amount of feto-maternal haemorrhage and thus the dose of Anti-D required).

- Group and Save – if blood group is unknown.

- Cross-match – if the clinical presentation is likely to warrant transfusion.

Biochemistry

These are performed to exclude hypertensive disorders including pre-eclampsia and HELLP syndrome, and any other organ dysfunction:

- Urea and electrolytes

- Liver function tests

Assess Fetal Wellbeing

In women above 26 weeks gestation, a cardiotocograph (CTG) should be performed to assess fetal wellbeing.

Imaging

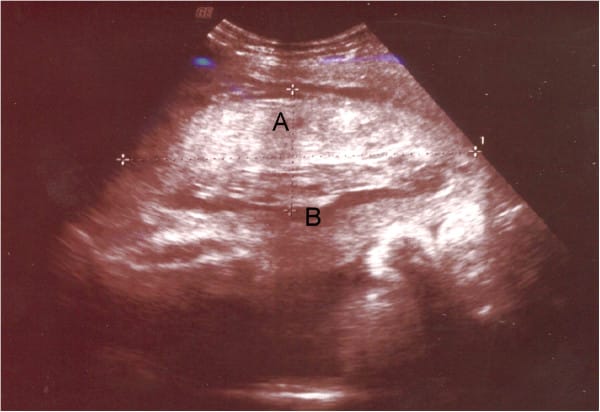

An ultrasound scan should be performed when patient is stable. In placental abruption, a retroplacental haematoma may be visible.

Ultrasound has a good positive predictive value, but a poor negative predictive value – and should not be used to exclude abruption.

Management

Any woman presenting with a significant antepartum haemorrhage should be resuscitated using an ABCDE approach. Do not delay maternal resuscitation in order to determine fetal viability.

The ongoing management of placental abruption is dependent on the health of the fetus:

- Emergency delivery – indicated in the presence of maternal and/or fetal compromise and usually this is by caesarean section unless spontaneous delivery is imminent or operative vaginal birth is achievable.

- Even if an in-utero fetal death has been diagnosed, a caesarean section may still be indicated if there is maternal compromise.

- Induction of labour – for haemorrhage at term without maternal or fetal compromise, induction of labour is usually recommended to avoid further bleeding.

- Conservative management – for some partial or marginal abruptions not associated with maternal or fetal compromise (dependant on the gestation and amount of bleeding).

In all cases, give anti-D within 72 hours of the onset of bleeding if the woman is rhesus D negative.