When considering delivery options in a patient with a previous Caesarean section, there are ultimately two care pathways for the patient:

- Vaginal birth after Caesarean section (VBAC)

- Planned elective repeat Caesarean

In this article, we shall look at risks and benefits of vaginal birth after Caesarean section, management of a VBAC delivery, and special considerations.

Risks and Benefits of VBAC

Approximately 20% of women worldwide will deliver via Caesarean section, and counselling patients about vaginal birth after Caesarean section is becoming increasingly important.

It is known that a planned vaginal birth after Caesarean section is clinically safe for the majority of women who have had one prior lower segment caesarean section (as per NICE, RCOG and ACOG recommendations).

The current success rates for attempted VBAC lie at 72-75% – however this is higher if the woman has had a previous vaginal delivery. Indeed, the strongest predictor of success in VBAC delivery is a successful previous VBAC (85-90% success rate).

More complex circumstances such as multiple pregnancy, macrosomia or maternal age >40 years old (see risk factors for uterine rupture below) require a more cautious approach and should discuss their care with a senior obstetrician.

A comparison of the risks associated with VBAC and elective repeat Caesarean section are listed in Table 1 below:

| VBAC | Elective Repeat Caesarean Section |

| If successful, shorter hospital stay and recovery | Longer recovery |

| Risk of uterine rupture – 0.5% | Almost negates risk of uterine rupture – <0.02% |

| 5% risk of anal sphincter injury | No risk of anal sphincter injury |

| Risk of maternal death – 4 in 100,000 | Risk of maternal death – 13 in 100,000 |

| If successful – good chance of successful future VBACs | Subsequent pregnancies likely to require caesarean section |

| 2-3% risk of transient respiratory difficulties for the neonate | 4-5% risk of neonatal respiratory morbidity |

| Risk of hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy (HIE) to the neonate – 0.08% | <0.01% risk of neonatal HIE |

| Risk of stillbirth beyond 39 weeks whilst awaiting spontaneous labour – 0.1% | With each caesarean delivery there is increased risk of placental problems (including accreta and praevia), and adhesion formation |

Table 1: Comparison of VBAC and elective Caesarean section.

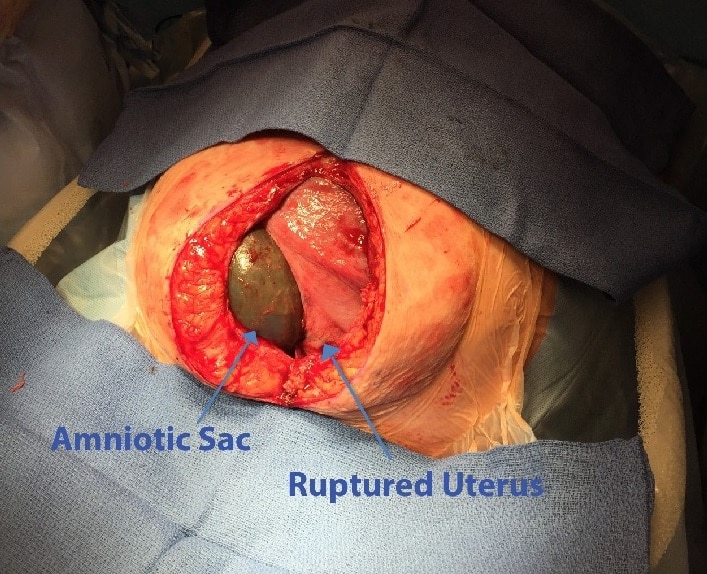

Uterine Rupture

Uterine rupture refers to a full-thickness disruption of the uterine muscle and overlying serosa. The fetus can be extruded from the uterus, resulting in fetal hypoxia and large internal maternal haemorrhage.

The greatest risk factor for uterine rupture is a previous Caesarean section – monitoring and recognition is a key principle of a VBAC delivery.

The risk factors for uterine rupture in VBAC include:

- Previous Caesarean section – classical (vertical) incisions carry the highest risk.

- Previous uterine surgery – such as myomectomy.

- Induction – (particularly with prostaglandins) or augmentation of labour.

- Obstruction of labour – this is an important risk factor to consider in developing countries.

- Multiple pregnancy.

- Multiparity.

Although infrequent, rupture is an obstetric emergency that requires an ABCDE management approach with delivery in theatre.

For more information see our article on uterine rupture.

Management of a VBAC Delivery

As described in Table 1, a VBAC is associated with certain risks. As such, there are some important recommendations regarding the management of such a delivery: [2]

- These women should deliver in a hospital setting with facilities for emergency caesarean and advanced neonatal resuscitation.

- There should be continuous CTG monitoring.

- Beware of additional analgesic requirements during the labour as may indicate impeding uterine rupture.

- Avoid induction where possible.

- If induction is required, the risk of uterine rupture is less using mechanical techniques (e.g. amniotomy) than induction with prostaglandins.

- Be cautious with augmentation (increased risk of uterine scar rupture)

- Any decisions about both induction and augmentation require input from a senior obstetrician.

- After 39 weeks an elective repeat caesarean is recommended delivery method.

There is a 2-3 times increased risk of rupture and 1.5 times increased risk of emergency Caesarean in induced/augmented labour vs spontaneous VBAC labour.

VBAC Contraindications

The contraindications for VBAC can be divided into (i) Absolute – under no circumstances should a VBAC be considered; and (ii) Relative – decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis by a senior obstetrician.

- Absolute – classical caesarean scar, previous uterine rupture and any other contraindications for vaginal birth that apply to the clinical scenario (for example placenta praevia).

- Relative – complex uterine scars or >2 prior lower segment Caesarean sections.

Key Points

- Most women with previous caesarean section have the option of a planned VBAC or elective repeat section.

- VBAC have relatively high success rates and these are even higher if they have had previous vaginal delivery.

- VBAC deliveries are classified as high risk and require close observation and careful management.

- There are both absolute and relative contraindications to VBAC to be aware of.

- Uterine rupture is an emergency that is of critical importance to recognise.

Further reading:

- Devarajan S, Talaulikar VS, Arulkumaran S. Vaginal birth after caesarean. Obstetrics, Gynaecology & Reproductive Medicine. April 2018. Volume 28. Issue 4. Pg 110-115

- Royal College of Obstetricians & Gynaecologists (2015) Birth after previous caesarean birth (Green-top guideline 45) – https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg45/

- Dodd JM, Crowther CA, Huertas E, Guise J, Horey D. Planned elective repeat caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for women with a previous caesarean birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 12