Recurrent miscarriage is defined by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists as ‘the occurrence of three or more consecutive pregnancies that end in miscarriage of the fetus before 24 weeks of gestation‘.

It affects 1–2% of women of reproductive age. The psychological impact of recurrent miscarriage is often distressing, and these women require considerable support and care.

In this article, we shall look at the causes, investigations and management of recurrent miscarriage.

Aetiology

Several factors have been associated with recurrent miscarriage, such as systemic disease, anatomical defects, and chromosomal abnormalities.

However, many of these associations are weak – and the cause of recurrent miscarriage remains unidentified in the majority of women.

Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Antiphospholipid syndrome refers to the association between antiphospholipid antibodies and vascular thrombosis or pregnancy failure/complications.

It is present in 15% of women with recurrent miscarriage. In these women, the live birth rate where there has been no pharmacological intervention has been reported to be as low as 10%.

Genetic Factors

There are two major genetic factors contributing to the risk of recurrent miscarriage:

- Parental chromosomal rearrangements – In approximately 2–5% of couples with recurrent miscarriage, one of the partners carries a balanced reciprocal or Robertsonian l chromosomal translocation.

- They are phenotypically normal, but their pregnancies are at an increased risk of miscarriage, secondary to an unbalanced chromosomal arrangement.

- Embryonic chromosomal abnormalities – In recurrent pregnancy loss, chromosomal abnormalities of the embryo account for 30–57% of further miscarriages.

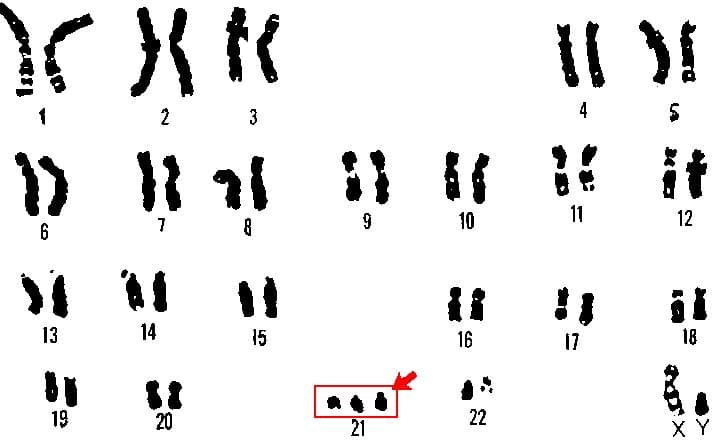

Fig 1 – Karyotyping performed on the products of conception, showing trisomy 21 – a embryonic genetic abnormality that is a strong risk factor for miscarriage.

Endocrine Factors

Diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease have both been associated with miscarriage (unless well controlled). Indeed, a high HBA1c at conception is linked with increased risk of miscarriage and fetal malformation.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is also associated with an increased risk of miscarriage. Though the exact mechanism remains unclear, it is possibly due to a combination of insulin resistance, hyperinsulinaemia and hyperandrogenaemia.

Anatomical Factors

Structural abnormalities of the female reproductive tract are a recognised factor in recurrent miscarriage. They include:

- Uterine malformations – such as septate, bicornuate or acuate uterus.

- Cervical weakness – where the cervix begins to efface and dilate before the pregnancy reaches term. The characteristic history is of a second-trimester miscarriage that is preceded by a spontaneous rupture of membranes or painless cervical dilatation.

- Acquired uterine abnormalities – such adhesions (Asherman’s syndrome) or fibroids.

Infective Agents

Any severe infection that results in bacteraemia or viraemia can lead to sporadic miscarriage, especially if there is pyrexia.

However, infection is an rare cause for recurrent miscarriage – as it is unlikely to be something that persists without signs or symptoms between pregnancy episodes.

Bacterial vaginosis in the first trimester of pregnancy is a risk factor for second-trimester miscarriage. Some individuals are predisposed to this, so screening in the first trimester and treatment (if appropriate) should be provided.

Inherited Thrombophilias

Inherited thrombophilias include Factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation and deficiencies of protein C/S and antithrombin III. They are more strongly associated with second trimester pregnancy loss, with the presumed mechanism being thrombosis of the uteroplacental circulation.

Fig 2 – The vasculature of the placenta. Uteroplacental thrombosis (secondary to inherited thrombophilias or APS), is thought to be causative in some second trimester pregnancy loss.

Risk Factors

The epidemiology of recurrent miscarriage has been well established. Risk factors include:

- Advancing maternal age – there is a decline in both the number and quality of the remaining oocytes. Advanced paternal age (>40) has also been identified as a risk factor for miscarriage but the cause is less well understood. By age alone, the risk of miscarriage at age 20 is 11%, rising to 25% at age 35-39. The risk increases to 51% for age 40-44 and 93% if aged more than 45.

- Number of previous miscarriages – an independent risk factor for recurrent pregnancy loss. The risk of a further miscarriage increases after each successive pregnancy loss, reaching approximately 40% after three consecutive pregnancy losses. A previous live birth does not preclude a woman developing recurrent miscarriage.

- Lifestyle – maternal cigarette smoking, moderate to heavy alcohol intake and caffeine consumption have been associated with an increased risk of spontaneous miscarriage in a dose-dependent manner. However, although current evidence is insufficient to confirm this association.

Investigations

Blood Tests

- Antiphospholipid antibodies – for the diagnosis of APS, it is mandatory that the woman has two positive tests at least 12 weeks apart for either lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies or anti-B2-glycoprotein antibodies.

- Inherited thrombophilia screen – including Factor V Leiden, prothrombin gene mutation and protein S deficiency.

Genetic Tests (Karyotyping)

- Cytogenetic analysis – this examines for any chromosomal abnormalities. It is performed on the products of conception of the third and subsequent consecutive miscarriage(s).

- Parental peripheral blood karyotyping – indicated when testing of products of conception reports an unbalanced structural chromosomal abnormality. It is performed on both partners.

Imaging

- Pelvic ultrasound scan – used to assess uterine anatomy.

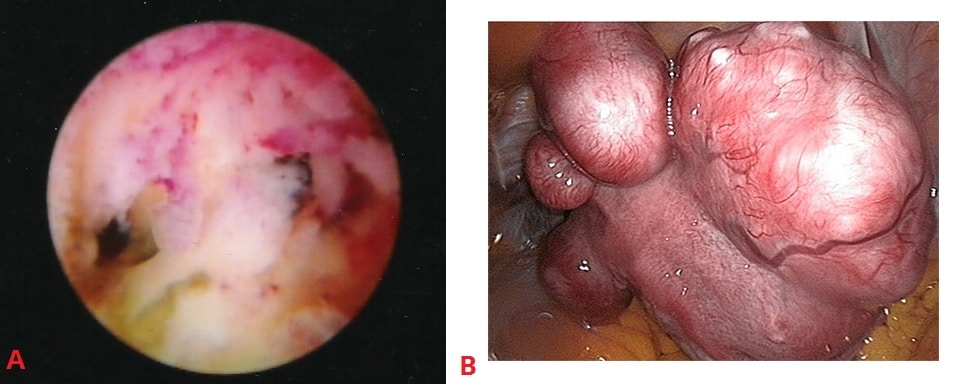

- If uterine anomalies are suspected, then further investigations may be required in order to confirm the diagnosis, by means of hysteroscopy, laparoscopy or three-dimensional pelvic ultrasound.

Note: There is no test to demonstrate cervical weakness. Cervical length can be measured by ultrasound but this does not equate to strength.

Fig 3 – Examples of uterine structural abnormalities. A – Intrauterine adhesions, visible on hysteroscopy. B- Uterine fibroids, visible on laparoscopy.

Management

All women with recurrent pregnancy loss should be referred to a specialist recurrent miscarriage clinic. Their management will depend on the underlying cause.

Genetic Abnormalities

Couples with an abnormal parental karyotype should be referred to a clinical geneticist.

Genetic counseling will offer the couple a prognosis for the risk of future pregnancies, and the opportunity for familial chromosome studies. Reproductive options will then include proceeding to a further natural pregnancy (with or without a prenatal diagnosis test), gamete donation and adoption.

Women with unexplained recurrent miscarriage are sometimes offered preimplantation genetic screening with in-vitro fertilisation treatment. However it has not been shown that this has any affect on live birth rates.

Anatomical Abnormalities

There are currently no published randomised trials to assess the benefit of surgical correction of uterine anomalies such as uterine septum resection on pregnancy outcome.

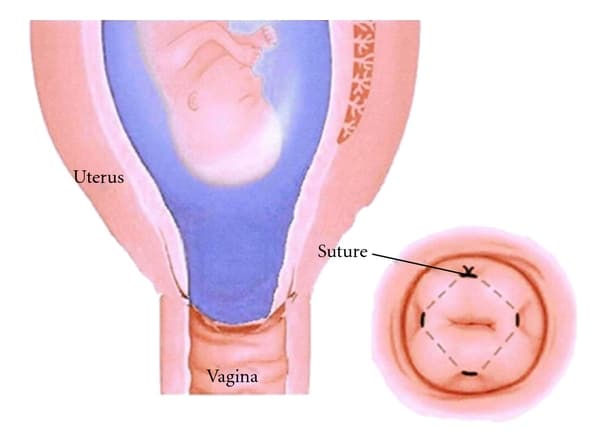

In some cases of cervical weakness, cervical cerclage (where a suture is used to close the cervix) may be indicated:

- Previous poor obstetric history (≥3x 2nd trimester losses).

- Cervical length shortening on USS (<25mm before 24/40 and a previous 2nd trimester loss).

- Symptomatic women with premature cervical dilatation and exposed fetal membranes in the vagina.

Complications of cervical cerclage include bleeding, membrane rupture, and stimulating uterine contractions. Hence, such a decision should be made with senior involvement and careful counselling of the woman.

Women with a history of second-trimester miscarriage and suspected cervical weakness who have not undergone cervical cerclage may be offered serial cervical sonographic surveillance.

Fig 4 – Cervical cerclage, where a suture is used to close the cervix.

Thrombophilias & Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Women with second-trimester miscarriage associated with inherited thrombophilias may have an improved live birth rate with heparin therapy during pregnancy.

Treatment with low-dose aspirin plus heparin should be considered in pregnant women with antiphospholipid syndrome. There is no role for empirical anticoagulation in patients without a diagnosis of APS.

Summary

- A significant proportion of those with recurrent miscarriage remain unexplained and should be referred to a recurrent miscarriage clinic.

- Women should be screened for antiphospholipid syndrome and inherited thrombophilias. A pelvic ultrasound is necessary.

- Cytogenetic analysis on products of conception should also be performed on subsequent pregnancy losses.

- Women with APS are advised to have low-dose aspirin plus heparin antenatally.

- Heparin therapy is also considered in women with second-trimester miscarriage associated with inherited thrombophilias.

- Cervical cerclage may be indicated in certain women and senior involvement and careful counselling is advised as a benefit is not entirely clear.