There are two main classifications of premature membrane rupture:

- Prelabour rupture of membranes (PROM) – the rupture of fetal membranes at least 1 hour prior to the onset of labour, at ≥37 weeks gestation.

- It occurs in 10-15% of term pregnancies, and is associated with minimal risk to the mother and fetus due to the advanced gestation.

- Pre-term prelabour rupture of membranes (P-PROM) – the rupture of fetal membranes occurring at <37 weeks gestation.

- It complicates ~2% of pregnancies and has higher rates of maternal and fetal complications. It is associated with 40% of preterm deliveries.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of PROM and P-PROM.

Aetiology and Pathophysiology

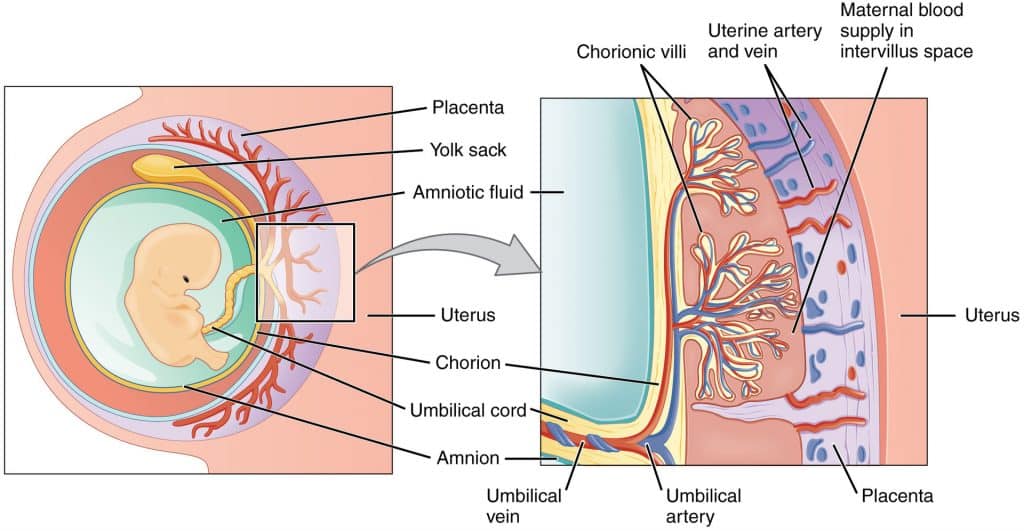

The fetal membranes consist of the chorion and the amnion. They are strengthened by collagen, and under normal circumstances, become weaker at term in preparation for labour.

The physiological processes underlying this weakening include apoptosis and collagen breakdown by enzymes.

In cases of prelabour rupture of membranes and P-PROM, a combination of factors can lead to the early weakening and rupture of fetal membranes:

- Early activation of normal physiological processes – higher than normal levels of apoptotic markers and MMPs in the amniotic fluid.

- Infection – inflammatory markers e.g. cytokines contribute to the weakening of fetal membranes. Approximately 1/3 of women with P-PROM have positive amniotic fluid cultures.

- Genetic predisposition

Risk Factors

The risk factors for pre labour rupture of membranes and P-PROM are listed in Table 1.

| Table 1 – Risk Factors Associated with PROM and P-PROM | |

| Smoking (especially < 28 weeks gestation).

Previous PROM/ pre-term delivery. Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy. Lower genital tract infection. |

Invasive procedures e.g. amniocentesis.

Polyhydramnios. Multiple pregnancy. Cervical insufficiency. |

Note: In many cases of PROM and P-PROM, there are no identifiable risk factors.

Clinical Features

In prelabour rupture of membranes, a typical history is of ‘broken waters’ – with women experiencing a painless popping sensation, followed by a gush of watery fluid leaking from the vagina.

However, the symptoms can often be more non-specific, such as gradual leakage of watery fluid from the vagina and damp underwear/pad, or a change in the colour or consistency of vaginal discharge.

On speculum examination, fluid draining from the cervix and pooling in the posterior vaginal fornix may be seen. To ensure an adequate examination, the woman should be laid on an examination couch for at least 30 minutes. This will allow pooling of any leaking amniotic fluid in the top of the vagina.

Additionally, a lack of normal vaginal discharge (‘washed clean’) can be suggestive of rupture of membranes. Asking the woman to cough during the examination can cause amniotic fluid to be expelled. A speculum is not required if amniotic fluid is seen draining from the vagina.

Note: In women with suspected P-PROM or PROM, it is important to avoid performing digital vaginal examinations until the woman is in active labour. This is because it has been shown that digital examination reduces the time between rupture of membranes and onset of labour (latency). This is likely due to the increased risk of introducing an ascending intrauterine infection.

Differential Diagnosis

In the assessment of suspected prelabour rupture of membranes, it is important to consider other diagnoses such as urinary incontinence (which is common in the later stages of pregnancy).

The important differential diagnoses are shown in Table 2.

| Table 2: PROM and P-PROM Differential Diagnoses | |

| Urinary incontinence.

Normal vaginal secretions of pregnancy. Increased sweat/ moisture around perineum. |

Increased cervical discharge (e.g. with infection).

Vesicovaginal vaginal fistula. Loss of mucus plug. |

Investigations

Diagnosis of PROM or P-PROM is usually made by; (i) maternal history of membrane rupture and; (ii) positive examination findings.

Tests for suspected rupture of membranes include:

- Actim-PROM (Medix Biochemica) – uses a swab test looking for IGFBP-1 (insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1) in vaginal samples. The concentration in amniotic fluid is 100 – 1000 times the concentration of maternal serum. This test is unlikely to be affected by blood contamination.

- Amnisure (QiaGen) – looks for Placental alpha microglobulin-1 (PAMG-1) which is present in the blood, amniotic fluid (in large concentrations) and cervico-vaginal discharge of pregnant women (in low concentrations with membranes intact).

Ultrasound is not used routinely, but may facilitate diagnosis in cases where it remains unclear. Reduced levels of amniotic fluid within the uterus are more suggestive of membrane rupture.

In all cases of premature membrane rupture, a high vaginal swab should be taken. It may grow Group B Streptococcus (GBS) which would indicate antibiotics in labour, or give information as to a potential cause for PPROM (bacterial vaginosis is commonly implicated).

Management

Rupture of the fetal membranes releases amniotic fluid – which acts to stimulate the uterus. Therefore, the vast majority of women with rupture of membranes will fall in to labour within 24-48 hours. There is very little that can be done to halt this.

If labour doesn’t start, it is important to consider the risks and benefits of expectant management versus induction of labour (IOL) when formulating an appropriate management plan for women with PROM:

- <34 weeks gestation – the balance would normally be in favour of aiming for increased gestation.

- >36 weeks gestation – if labour does not start, induction of labour ought to be considered at 24–48 hours. This is because the risk of infection outweighs any benefit of the fetus remaining in utero.

- 34 – 36 weeks – Historically the aim was to get the pregnancy to 36 weeks if there was no evidence of infection. However, with improvements in neonatal care (and evidence for poorer outcomes in babies if there is maternal infection), management has shifted towards 34 weeks and induction of labour once there has been a course of steroids.

With P-PROM, if there is no concern for developing infection and there are no signs of labour, it may be possible to continue conservative management at home.

| Table 3 – Principles of Management of PROM and P-PROM | |

| > 36 weeks

|

Monitor for signs of clinical chorioamnionitis.

Clindamycin/penicillin during labour if GBS isolated. Watch and wait for 24 hours (60% of women go into labour naturally), or consider induction of labour. IOL and delivery recommended if greater than 24 hours (but women can wait up to 96 hours – beyond this is their choice after counselling) |

| 34 – 36 weeks

|

Monitor for signs of clinical chorioamnionitis, and advise patient to avoid sexual intercourse (can increase risk of ascending infection).

Prophylactic erythromycin 250 mg QDS for 10 days. Clindamycin/penicillin during labour if GBS isolated. Corticosteroids if between 34 and 34+6 weeks gestation. IOL and delivery recommended. |

| 24 – 33 weeks

|

Monitor for signs of clinical chorioamnionitis, and advise patient to avoid sexual intercourse.

Prophylactic Erythromycin 250 mg QDS for 10 days. Corticosteroids (as less than 34+6). Aim expectant management until 34 weeks. |

Complications

The outcome of PROM generally correlates with the gestational age of the fetus.

The majority of women at term will enter spontaneous labour within 24 hours after membrane rupture, but there is a greater latency period the younger the gestational age. This pre-disposes to a greater risk of maternal and fetal complications:

- Chorioamnionitis – inflammation of the fetal membranes, due to infection. The risk increases the longer the membranes remain ruptured and baby undelivered.

- Oligohydramnios – this is particularly significant if the gestational age is less than 24 weeks, as it greatly increases the risk of lung hypoplasia.

- Neonatal death – due to complications associated with prematurity, sepsis and pulmonary hypoplasia.

- Placental abruption

- Umbilical cord prolapse

Summary

- PROM is defined as rupture of membranes > 1 hour prior to the onset of labour occurring ≥ 37 weeks gestation.

- P-PROM is rupture of the amniotic sac < 37 weeks gestation.

- Diagnosis of membrane rupture is usually from maternal history and sterile speculum examination.

- IOL and delivery should be considered where gestational age > 34 weeks and expectant management < 34 weeks gestation.

- P-PROM is associated with much higher rates of complications than PROM. The main causes of neonatal mortality include complications associated with prematurity, sepsis and pulmonary hypoplasia.