A breech presentation is when the fetus presents buttocks or feet first (rather than head first – a cephalic presentation).

It has significant implications in terms of delivery – especially if it occurs at term (>37 weeks). Breech deliveries carry a higher perinatal mortality and morbidity, largely due to birth asphyxia/trauma, prematurity and an increased incidence of congenital malformations.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, investigations and management of a breech presentation.

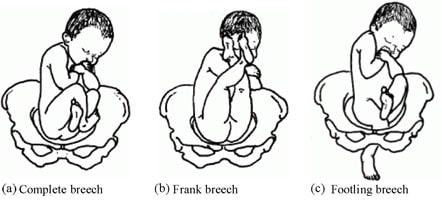

Types of Breech Presentation

In a breech presentation, the fetus presents ‘bottom down’. There are three main types, depending on the position of the legs:

- Complete (flexed) breech – both legs are flexed at the hips and knees (fetus appears to be sitting ‘crossed-legged’).

- Frank (extended) breech – both legs are flexed at the hip and extended at the knee. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

- Footling breech – one or both legs extended at the hip, so that the foot is the presenting part.

Approximately 20% of babies are breech at 28 weeks gestation. The majority of these revert to a cephalic presentation (head down) spontaneously, and only 3% are breech at term.

Aetiology and Risk Factors

Most breech presentations seem to be chance occurrences. However, in up to 15% of cases, it may be due to fetal or uterine causes. The risk factors are listed below:

| Uterine | Fetal |

| Multiparity

Uterine malformations (e.g. septate uterus) Fibroids Placenta praevia

|

Prematurity

Macrosomia Polyhydramnios (raised amniotic fluid index) Twin pregnancy (or higher order) Abnormality (e.g. anencephaly) |

Clinical Features

The diagnosis of breech presentation is of limited significance prior to 32-35 weeks (as the fetus is likely to revert to a cephalic presentation before delivery).

Breech presentation is usually identified on clinical examination. Upon the palpating the abdomen, the round fetal head can be felt in the upper part of the uterus, and an irregular mass (fetal buttocks and legs) in the pelvis.

Breech presentation can also be suspected if the fetal heart is auscultated higher on the maternal abdomen.

In around 20% of cases, breech presentation is not diagnosed until labour. This can present with signs of fetal distress, such as meconium-stained liquor. On vaginal examination, the sacrum or foot may be felt through the cervical opening.

Differential Diagnosis

There are two main differential diagnoses for a breech presentation:

- Oblique lie – the fetus is positioned diagonally in the uterus, with the head or buttocks in one iliac fossa.

- Transverse lie – the fetus is positioned across the uterus, with the head on one side of the pelvis and the buttocks on the other. The shoulder is usually the presenting part.

The other important diagnosis to consider is unstable lie. This is where the presentation of the fetus changes from day-to-day (and can include breech presentation). Unstable lie is more likely if there is known polyhydramnios or the woman is multiparous.

Investigations

Any suspected breech presentation should be confirmed by an ultrasound scan – which can also identify the type of breech (flexed/extended/footling). It can also reveal any fetal or uterine abnormalities that may predispose to breech presentation.

Management

At term, the options for management of breech presentation are (i) external cephalic version; (ii) Caesarean section; or iii) vaginal breech birth.

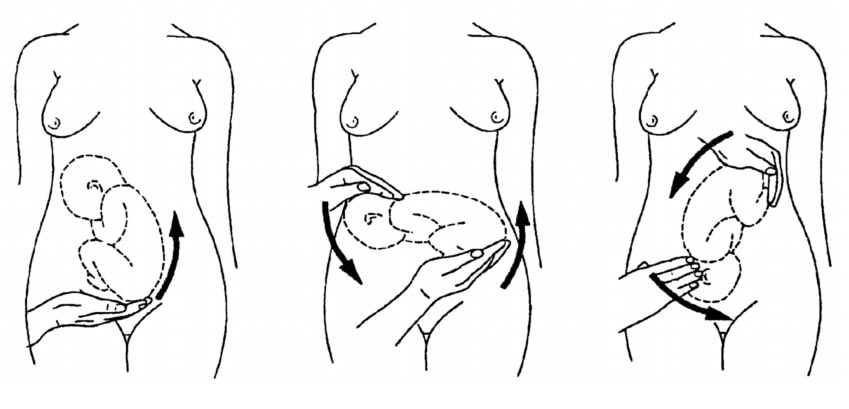

External Cephalic Version

External cephalic version is the manipulation of the fetus to a cephalic presentation through the maternal abdomen. This, if successful, can enable an attempt at vaginal delivery.

It has an approximate 50% success rate (40% success rate in a primiparous woman, and a 60% success rate in a multiparous woman). In contrast, only 10% of breech presentations spontaneously revert to cephalic in primiparous women.

ECV should be offered from 37 weeks gestation. In primiparous women, ECV can be offered from 36 weeks gestation.

Complications of ECV include transient fetal heart abnormalities (which revert to normal), and rarer complications such as more persistent heart rate abnormalities (e.g fetal bradycardia), and placental abruption. The risk of the woman needing an emergency Caesarean is around 1/200.

There is no consensus on the contraindications to ECV. Women should be informed that ECV after one Caesarean section delivery has no greater risk compared to ECV performed on an unscarred uterus.

Caesarean Section

If the external cephalic version is unsuccessful, contraindicated, or declined by the woman, current UK guidelines advise an elective Caesarean delivery.

This is based on evidence that perinatal morbidity and mortality is higher in cases of planned vaginal breech birth (compared to Caesarean) in term babies. There is no significant difference in maternal outcomes between the two groups.

The evidence for preterm babies is less clear, but generally C/S is preferred due to the increased head to abdominal circumference ratio in preterm babies.

Vaginal Breech Birth

A woman may still choose to aim for a vaginal breech delivery. Additionally, a small proportion of women with breech presentation present in advanced labour – with vaginal delivery the only option.

A contraindication to vaginal breech delivery is footling breech, as the feet and legs can slip through a non-fully dilated cervix, and the shoulders or head can then become trapped.

The most important advice when conducting a vaginal breech delivery is “hand off the breech”. This is because putting traction on the baby during delivery can cause the fetal head to extend, getting it trapped during delivery. The fetal sacrum does need to be maintained anteriorly, which can be done by holding the fetal pelvis. However, occasionally the baby does not deliver spontaneously, and some specific manoeuvres are required:

- Flexing the fetal knees to enable delivery of the legs.

- Using Lovsett’s manoeuvre to rotate the body and deliver the shoulders.

- Using the Mauriceau-Smellie-Veit (MSV) manoeuvre to deliver the head by flexion.

- The delivery of the aftercoming head can be challenging, but if MSV fails forceps can be used.

Complications

A major complication of breech presentation is cord prolapse (where the umbilical cord drops down below the presenting part of the baby, and becomes compressed). The incidence of cord prolapse is 1% in breech presentations, compared to 0.5% in cephalic presentations.

Other complications include:

- Fetal head entrapment

- Premature rupture of membranes

- Birth asphyxia – usually secondary to a delay in delivery.

- Intracranial haemorrhage – as a result of rapid compression of the head during delivery.

Summary

- 3% of babies are in breech presentation at term (>37 weeks), with a higher incidence in preterms.

- The main implication of breech presentation is on delivery.

- External cephalic version may be offered to turn the baby via the maternal abdomen to cephalic presentation. This is successful in around 50% of cases.

- If the baby remains breech, the options for delivery are by Caesarean section or vaginal breech.

- Current guidelines recommend Caesarean delivery, but a vaginal breech birth is possible with an experienced obstetrician or midwife.