A Bartholin’s cyst is a fluid-filled sac within one of the Bartholin’s glands of the vagina.

The exact incidence of Bartholin’s cysts and abscesses is uncertain, but abscesses account for 2% of all gynaecological visits a year. Asymptomatic cysts may occur in up to 3% of women, although they often do not present to healthcare services.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of a Bartholin’s cyst or abscess.

Aetiology and Pathophysiology

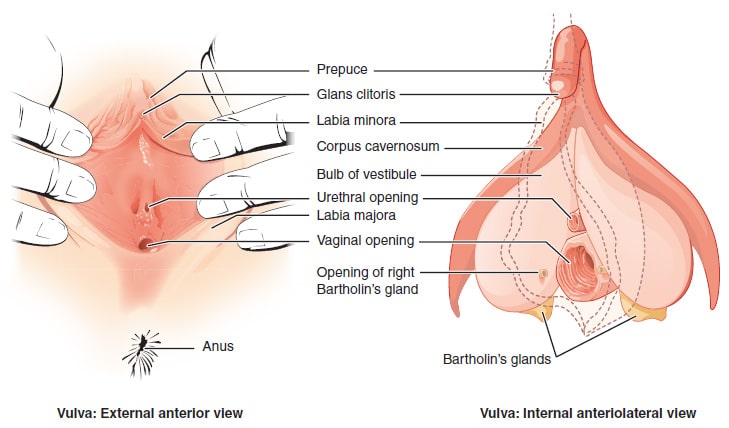

The Bartholin’s glands (greater vestibular glands) are located deep to the posterior aspect of the labia majora. Their openings are located either side of the vaginal orifice, within the vestibule of the vagina (approximately 4 o’clock and 8 o’clock positions), just below the hymenal ring. They secrete mucus to lubricate the vagina.

A build-up of mucus secretions can cause the duct of the gland to become blocked, from which a cyst can develop. The cyst itself can become infected, and if untreated, develop into an abscess.

The infective organisms are usually aerobic, with Escherichia coli, MRSA and STI’s the most common.

Risk Factors

Bartholin’s cysts characteristically occur in nulliparous women of child-bearing age. Other risk factors include:

- Personal history of Bartholin’s cyst

- Sexually active (STIs can cause a Bartholin’s cyst or abscess)

- History of vulval surgery

Clinical Features

Small Bartholin’s cysts are often asymptomatic. If they become large, they can cause vulvar pain (particularly when walking and sitting), and superficial dyspareunia (pain during sexual intercourse).

The cyst can undergo spontaneous rupture – after which the patient typically experiences a sudden relief of pain.

Bartholin’s abscesses typically present with acute onset of pain, and/or difficulty passing urine.

On examination, a unilateral labial mass will be observed. This typically arises from the posterior aspect of the labia majora, although a large cyst or abscess can expand anteriorly.

- Bartholin’s cyst – typically soft, fluctuant and non-tender

- Bartholin’s abscess – typically tense and hard, with surrounding cellulitis

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a mass in the labial or vulval region includes:

- Bartholin’s gland carcinoma – primary carcinoma is rare (approximately 0.1-5% of vulvar malignancies).

- Bartholin’s benign tumour – such as adenomas and nodular hyperplasia. These are rarer than Bartholin’s carcinoma.

- Other types of cyst – e.g. sebaceous cyst, Skene’s duct cyst, mucous cyst

- Other solid masses – e.g. fibroma, lipoma, leiomyoma

Investigations

The diagnosis of a Bartholin’s cyst or abscess is often a clinical one, and further investigations are not routinely required.

However – if the woman is over 40 years of age, a biopsy of the cyst should be considered (especially if there are solid components to the swelling) – this is to exclude vulval carcinoma.

If there are any indications of a sexually transmitted infection, endocervical and high vaginal swabs should be taken.

Management

If the cyst is small and asymptomatic, no treatment is required. Warm baths can be recommended to the patient, as they may stimulate spontaneous rupture.

Treatment is usually by Word Catheter or marsupialisation. There is no high quality evidence comparing different treatment options. However, simple incision and drainage without marsupialisation or placement of a Word catheter means that the accumulation of fluid is likely to reoccur (due to further outflow obstruction).

- Word Catheter – an incision is made into the cyst or abscess, and a catheter is inserted. The tip is inflated with 2-3ml of saline. It is left in place for 4-6 weeks to allow epithelisation of the surgically created tract. This technique is not suitable for deep cysts or abscesses. It can be performed under local anaesthesia in a clinic.

- Complications include infection, recurrence, dyspareunia and scarring.

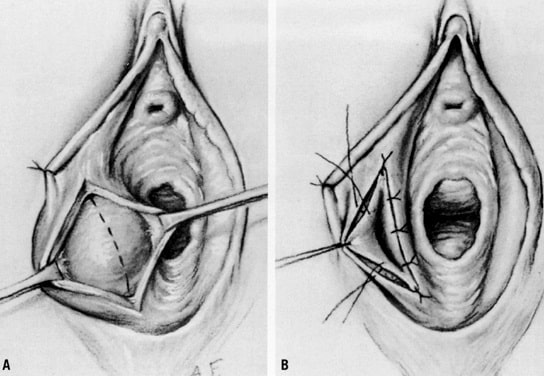

- Marsupialisation – a vertical incision is made into the cyst, behind the hymenal ring, allowing for spontaneous drainage of the cavity. The cyst wall is then everted and approximated to the end of the vaginal mucosa by sutures. This requires a general anaesthetic to achieve good marsupialisation

- Complications include bleeding/haematoma, dyspareunia and infection.

Less commonly used techniques include silver nitrate cautery, carbon dioxide laser and needle aspiration. Complete excision of the gland is rarely performed – and usually only in cases of suspected malignancy.

There is no evidence to routinely pack the cavity after any of these procedures.

Note: Antibiotics are generally not used in the management of a Bartholin’s cyst or abscess. However, they can be considered if the patient is systemically unwell, or immunocompromised.