Anaemia refers to a deficiency of haemoglobin (Hb) in the blood. It is a common problem in pregnancy, estimated to affect 38% of women worldwide.

UK guidelines define anaemia in pregnancy as a first trimester haemoglobin less than 110 g/l, second/third trimester Hb less than 105 g/l, or a postpartum Hb less than 100 g/l.

During pregnancy, both the plasma volume and red blood cell mass increase. However, the plasma volume increases disproportionately – resulting in a haemodilution effect. This predisposes pregnant women to developing anaemia.

In this article, we shall look at the causes, clinical features, and management of anaemia during pregnancy.

Risk Factors

The risk factors for developing anaemia during pregnancy include:

- Haemoglobinopathies

- Thalassaemia

- Sickle cell disease

- Increasing maternal age

- Low socioeconomic status

- Poor diet

- Anaemia during previous pregnancy

Clinical Features

Common symptoms of anaemia include dizziness, fatigue and dyspnoea. However, it should be noted that these are also all features of a normal pregnancy. Anaemia can be asymptomatic, and may only be detected on a full blood count.

On examination, the patient may have pallor (best identified in the mucosa of the tongue and mouth). Less common features include koilonychia (spoon-shaped nails) and angular cheilitis (ulceration at the corners of the mouth).

Differential Diagnosis

Anaemia has a wide variety of possible causes. The differential diagnoses can be categorised by the mean corpuscular volume (MCV):

| Microcytic (MCV ≤76) | Normocytic (MCV 76-96) | Macrocytic (MCV ≥96) |

| Iron deficiency

Thalassaemia Sideroblastic anaemia |

Anaemia of chronic disease

Marrow infiltration Haemolytic anaemia Chronic kidney disease |

B12 deficiency

Folate deficiency Alcohol consumption Recticulocytosis Hypothyroidism |

Table 1 – The differential diagnoses for anaemia. Note that the cut-offs for MCV will vary between different laboratories.

Investigations

The principle investigation in anaemia is a full blood count, assessing the haemoglobin level and mean corpuscular volume.

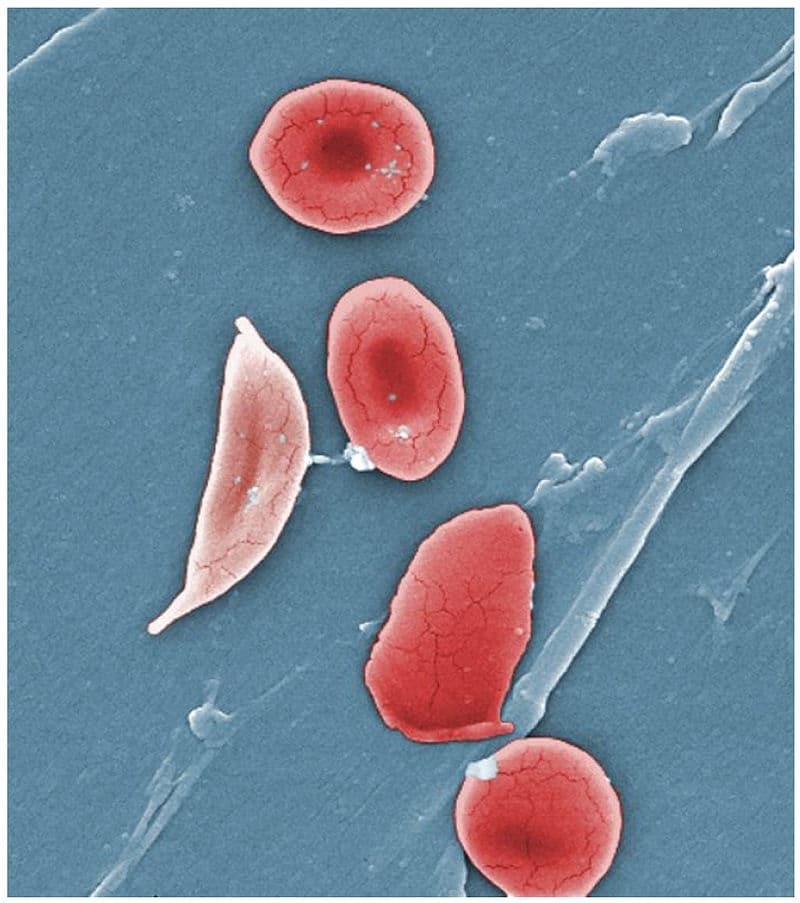

Fig 2 – Coloured scanning electron micrograph, showing a sickled red blood cell.

Serum ferritin is not routinely measured – even in cases where iron deficiency anaemia is suspected. One exception to this is in areas with a high prevalence of haemoglobinopathies.

Haemoglobinopathy screening should be considered in patients with confirmed anaemia and an unknown haemoglobinopathy status.

Further investigations are dependent on the suspected cause:

- Folate deficiency– serum folate (<7 nmol/L indicates deficiency – although this may vary between different laboratories).

- Beta thalassaemia– haemoglobin electrophoresis (HbA2 >3.5% is diagnostic).

- Sickle cell disease– haemoglobin electrophoresis (HbA is absent, 80-95% HbSS and 2-20% HbF).

Screening

In the UK, it is recommended that all pregnant women are screened for anaemia at booking and at 28 weeks of gestation.

In multiple pregnancies, additional screening should be performed at 20-28 weeks.

Management

Iron Deficiency Anaemia

If the anaemia is micro- or normocytic, then the most likely cause is iron deficiency. In these women, a trial of oral iron (100-200mg) should be considered as first line management, and as a diagnostic test. A full blood count should be repeated after two weeks of treatment, examining for an increase in haemoglobin.

A parental iron infusion (Ferinject®) should be considered if compliance is poor or there is evidence of malabsorption.

| Preparation | Dose per tablet | Elemental Iron | No of tablets per day |

| Pregaday | 100mg | 2 | |

| Ferrous sulphate | 200mg | 65mg | 3 |

| Ferrous gluconate | 300mg | 35mg | 6 |

| Ferrous fumarate | 210mg | 68mg | 3 |

Table 2 – Amount of elemental iron in common preparations

Other Causes

Management of other types of anaemia in pregnancy is dependent on the underlying cause:

- Folate deficiency– folate supplementation; usually 5mg folic acid once daily. This can be increased up to three times a day if required.

- Beta thalassaemia– folate supplementation and blood transfusions as required; aiming for a Hb of 80g/L during pregnancy, and 100g/L at delivery (depending on symptoms).

- Sickle cell disease– folate supplementation and iron supplementation if there is laboratory evidence of iron deficiency.

Summary

- Anaemia is a common problem in pregnancy.

- Clinical features include dizziness, fatigue and dyspnoea, but patients may be asymptomatic.

- Hb and MCV are key investigations.

- Iron deficiency anaemia should be initially treated with a diagnostic trial of oral iron supplementation.