Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a collective term that describes deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).

In the UK, venous thromboembolism is a leading cause of maternal mortality – responsible for approximately 1/3 of maternal deaths.

Pregnancy is a major risk factor for VTE, resulting in a 4-5x increased risk. This is thought to be due to changes in the levels of some of the proteins of the clotting cascade (such as increased fibrinogen, and decreased protein S). These changes become more pronounced as the pregnancy progresses, and thus the period of highest risk is post-partum.

In this article, we shall look at the risk factors, clinical features and management of a patient with VTE during pregnancy.

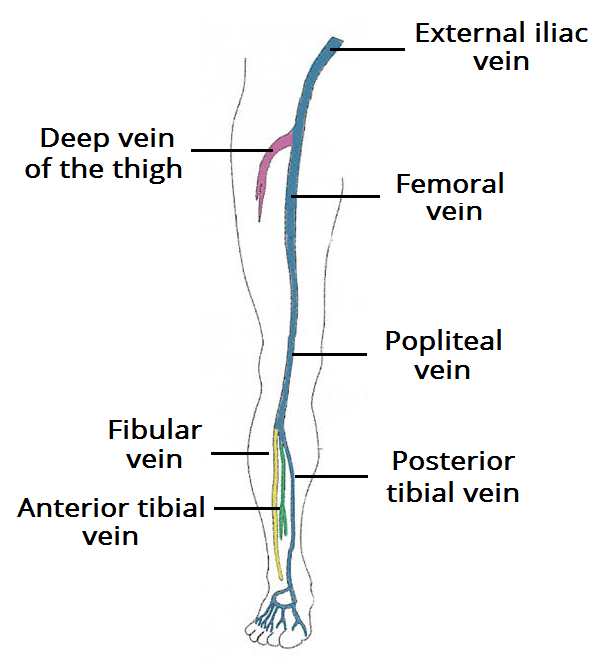

Fig 1- The deep venous system of the lower limb. In pregnant women, the majority of DVTs form in the proximal veins, and the left leg is most commonly affected.

Risk Factors

Whilst pregnancy itself is a major risk factor for developing a VTE, there are additional factors that can further increase risk. They can be divided into pre-existing factors, obstetric factors and transient factors:

| Pre-existing Factors | Obstetric Factors | Transient Factors |

| Thrombophilia (e.g Antiphospholipid syndrome)

Medical co-morbidities (e.g cancer) Age >35 years BMI >30 kg/m2 Parity >3 Smoking Varicose veins Paraplegia |

Multiple pregnancy

Pre-eclampsia Caesarean section Prolonged labour Stillbirth Preterm birth PPH |

Any surgical procedure in pregnancy of puerperium

Dehydration (e.g hyperemesis) Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome Admission or immobility Systemic infection Long distance travel |

Table 1 – VTE risk factors.

Clinical Features

Fig 2 – Deep vein thrombosis in the right leg.

Deep Vein Thrombosis

The most common presenting symptom of a deep vein thrombosis is unilateral leg pain and swelling. Other clinical features include pyrexia, pitting oedema, tenderness or prominent superficial veins. It is important to note that some of these symptoms can also be features of a normal pregnancy.

In pregnant women, the majority of DVTs form in the proximal veins, with the left leg most commonly affected. This is thought to be due to the compression effect of the uterus on the left iliac vein.

Pulmonary Embolism

The key clinical features of a pulmonary embolism are sudden onset dyspnoea, pleuritic chest pain, cough, and (rarely) haemoptysis.

Clinically, the patient may have tachycardia, tachypnoea, pyrexia, a raised JVP (rare), or pleural rub or pleural effusion (rare). It is important to examine for any signs of DVT in a patient with suspected PE.

Differential Diagnosis

Deep Vein Thrombosis

The differential diagnoses for unilateral leg pain and swelling include cellulitis, ruptured Baker’s cyst and superficial vein thrombophlebitis. It also can be a feature of normal pregnancy.

Note: If a superficial vein thrombophlebitis extends to near the deep vein junction, it is treated as a DVT.

Pulmonary Embolism

There are a large number of possible diagnoses for sudden onset dyspnoea and chest pain. Acute coronary syndromes, aortic dissection, pneumonia and pneumothorax should be excluded.

Investigations

In a suspected DVT or PE, a basic set of blood tests should be performed – including FBC, U&Es, LFTs and a coagulation screen. These will be required before any treatment is initiated.

A rise in D-dimer is normal in pregnancy, and so testing is not recommended in this scenario.

Deep Vein Thrombosis

The definitive investigation for a suspected DVT is a compression duplex ultrasound scan. If the scan is negative, but clinical suspicion remains high, the test can be repeated 1 week later (whilst maintaining the patient on anticoagulation).

Pulmonary Embolism

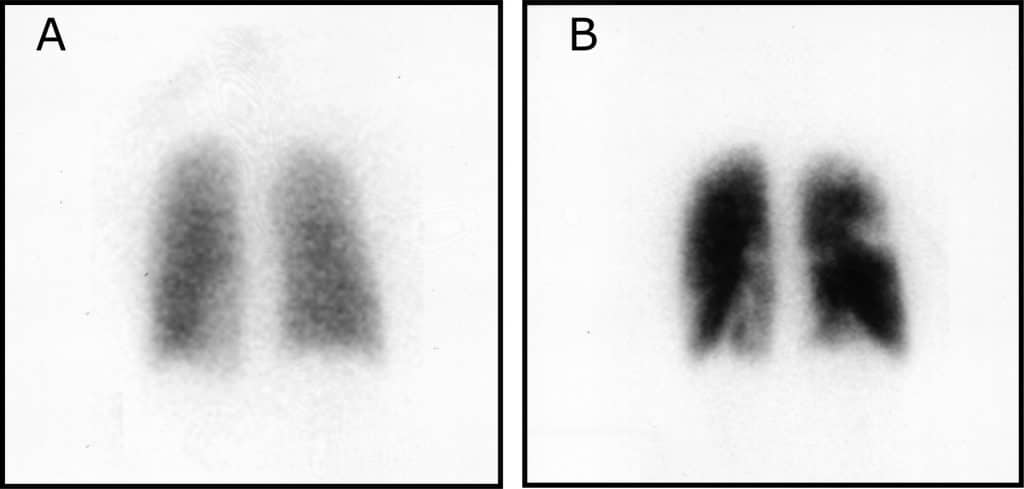

Women presenting with features of a PE should be initially assessed with an ECG and chest x-ray. Arterial blood gas can be considered, but is thought to be of limited diagnostic value.

The definitive diagnosis is via CTPA or V/Q scan. Women should be counselled that the V/Q scan is associated with an increased risk of childhood cancer, but carries a lower risk of breast cancer.

If a woman presents with clinical features of DVT and PE, a duplex ultrasound should be initially performed. If this is positive, the CTPA or V/Q scan does not need to be performed. This saves the woman from unnecessary radiation exposure.

Management

All women with symptoms of VTE should have low-molecular weight heparin (LMWH) started immediately until the diagnosis is excluded by definitive testing. The dose should be titrated against the woman’s booking weight.

In confirmed venous thromboembolism, anticoagulation should be maintained throughout the pregnancy, until 6-12 weeks post-partum. Women should be advised to omit their dose 24 hours before any planned induction of labour or caesarean section. Furthermore, they should not take their dose if they think they are going into labour.

In the UK, LMWH is the anticoagulant of choice. Alternatives include unfractionated heparin and new oral anticoagulants (e.g rivaroxaban). Warfarin should never be used in the treatment of VTE during pregnancy as it is teratogenic, and can lead to foetal loss through haemorrhage.

When venous thromboembolism occurs at term, the use of IV unfractionated heparin should be considered. This can be discontinued 6 hours before planned induction of labour or caesarean section (compared to 24 hours for LMWH).

Resuscitation

Patients suffering from cardiogenic shock secondary to massive PE should be resuscitated in an ABCDE approach (airway, breathing, circulation, disability).

Consider immediate thrombolysis in these patients, and treatment with IV unfractionated heparin.

Prophylaxis

All women should be assessed for their risk of VTE early in the pregnancy. This assessment should be repeated in the intrapartum and postnatal periods.

Whilst guidelines vary between organisations, the general principles of VTE prophylaxis in pregnancy are:

- Women should be assessed for their risk of developing a VTE using the risk factors in Table 1.

- In the UK, pregnant women are offered thromboprophylaxis if they have ≥4 risk factors in the first 2 trimesters, ≥3 in the 3rd trimester, and ≥2 in the post-partum period.

- Any woman receiving thromboprophylaxis antenatally should continue anticoagulation until at least 6 weeks postpartum (as the immediate postnatal period carries the highest risk).

- A 10-day course of LMWH should be considered in all women who have had a Caesarean section (particularly in emergency cases).

Previous VTE and Thrombophilia

Women with previous VTE or known thrombophilia carry a particularly high risk of developing a VTE during pregnancy, and should be managed in collaboration with a haematologist.

| Previous VTE (provoked from major surgery) | Thromboprophylaxis with LMWH from 28 weeks onward |

| Other previous VTE | Thromboprophylaxis with LMWH throughout antenatal period |

| Known antithrombin deficiency | Thromboprophylaxis with high dose LMWH (usually 50%, 75% or full treatment dose) |

| Known antiphospholipid syndrome | Thromboprophylaxis with high dose LMWH (usually 50%, 75% or full treatment dose) |

Table 2 – Prevention of VTE in those with previous VTE or thrombophilia.